FULL TEXT: Retired SC Justice Antonio Carpio delivers keynote address at a forum on the West Philippine Sea

Speaking for the first time after retiring from the Supreme Court, Justice Antonio T. Carpio delivered the keynote address at a forum on a Code of Conduct (COC) on the West Philippine Sea.

We are reproducing Justice Carpio’s speech in full below.

KEYNOTE SPEECH

October 28, 2019

Justice Antonio T. Carpio (Ret.)

Good morning to everyone. I wish to thank the ADR Institute for inviting me here this morning to discuss with you a topic that has been my advocacy for almost a decade now.

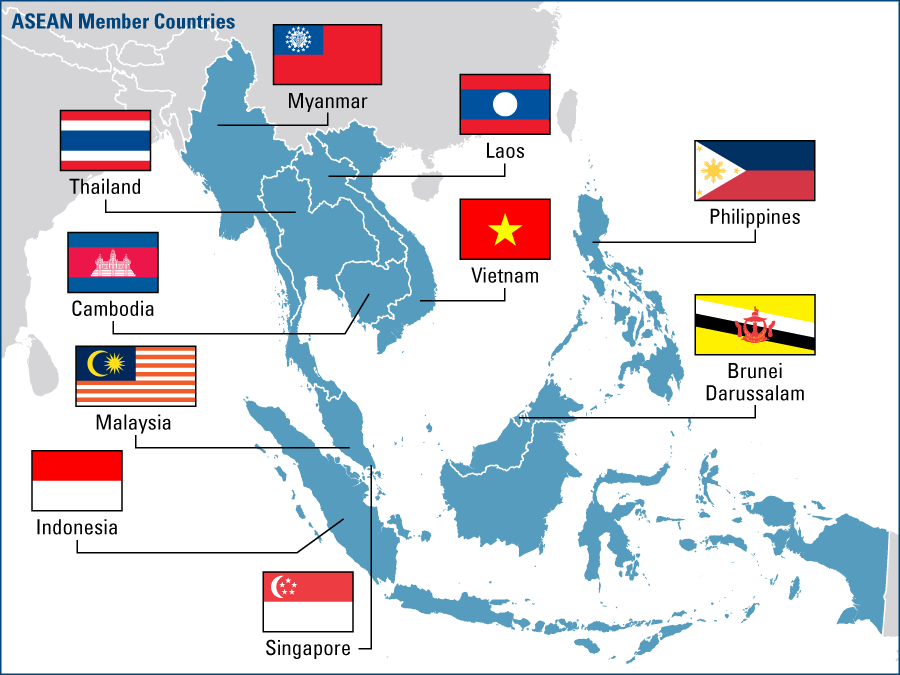

Upon its founding in 1967, ASEAN issued the ASEAN Declaration stating the aims and purposes of ASEAN, which are “to accelerate the economic growth, social progress and cultural development” within the ASEAN region, and “to promote regional peace and stability through abiding respect for justice and the rule of law.” In 1995, the ASEAN Heads of State and Government re-affirmed that “cooperative peace and shared prosperity shall be the fundamental goals of ASEAN.”

Thus, the ultimate goal of ASEAN is peace and stability and shared economic progress within ASEAN. When it comes to peace and stability, abiding respect for justice and the rule of law is the recognized vehicle to achieve cooperative peace within ASEAN.

To achieve peace and stability within ASEAN requires an overarching architecture for the compulsory settlement of disputes among its member-states on territorial and maritime issues. This architecture is an essential and necessary condition for long-term peace within ASEAN. Unfortunately, this overarching architecture on a compulsory dispute settlement mechanism has yet to be established.

ASEAN has no dispute settlement mechanism for territorial or maritime disputes. The Treaty of Amity and Cooperation for Southeast Asia does not provide for an adjudicatory dispute settlement mechanism, much less a compulsory or binding one.

For territorial disputes within ASEAN, ASEAN member-states have resorted to the voluntary dispute settlement mechanism under the International Court of Justice, a settlement which requires voluntary submission by the disputant states to arbitration.

Thus, in the Pedra Branca territorial dispute, decided by the ICJ in 2008, both Singapore and Malaysia voluntarily submitted the dispute to ICJ arbitration. In the Ligitan and Sipadan territorial dispute, decided by the ICJ in 2002, both Malaysia and Indonesia voluntarily submitted the dispute to ICJ arbitration. The Philippines intervened in the Ligitan and Sipadan arbitration, but our intervention was rejected by the ICJ.

For maritime disputes, ASEAN coastal member-states that are also members of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea or UNCLOS, can bring their intra-ASEAN maritime disputes to the compulsory dispute mechanism under UNCLOS. So far, no ASEAN member-state has sued another ASEAN member-state before an UNCLOS tribunal.

The pressing problem facing ASEAN, however, is not any territorial or maritime dispute between or among ASEAN member-states, but a territorial and maritime dispute between five ASEAN member-states and China, which claims about 85.7 percent of the entire South China Sea under its so-called nine-dashed line. This Chinese claim, insofar as the maritime dispute is concerned, has been totally rejected by an UNCLOS tribunal. However, this has not stopped China from seizing or encroaching on, though intimidating grey zone tactics, the Exclusive Economic Zones of five ASEAN coastal states: the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei and Indonesia.

While the Spratlys dispute also involve overlapping territorial claims among the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia and Brunei, these ASEAN member-states have an informal understanding to maintain the status quo in the Spratlys. China refuses to respect the status quo in the Spratlys and has been aggressively intimidating other claimant states, notably the Philippines, Vietnam and Malaysia, through grey zone tactics – which are acts of intimidation exercised by paramilitary vessels and forces under the direction of the Chinese military.

What should the five ASEAN member-states do to counter this Chinese intimidation and in general to enforce the arbitral ruling which redounds immeasurably to the benefit of all the five ASEAN member-states?

First, the five ASEAN member-states can formalize their informal understanding by signing a convention that among them their territorial disputes in the Spratlys shall be settled peacefully through negotiations, and by special agreement of the parties, through arbitration in accordance with international law. In the meantime, the status quo shall be maintained and no force, threat of force, or intimidating grey zone tactics, shall be used by the parties. What constitute grey zone tactics should be clearly defined in the convention. This will isolate China as the only disputant state resorting to grey zone tactics and refusing to maintain the status quo.

Second, the five ASEAN member-states can enter into a convention declaring that all the high-tide geologic features in the Spratlys generate only territorial seas and none of these geologic features generate an Exclusive Economic Zone as ruled by the arbitral tribunal at The Hague in the South China Sea arbitration. As this will guide outside powers on the extent of the exercise of freedom of navigation and overflight in the Spratlys area, this convention can be opened for accession by outside powers like the U.S., U.K., France, Australia, Japan, India, Canada, states which regularly exercise freedom of navigation and overflight in the South China Sea. Such a convention will enforce the arbitral ruling by state practice.

Third, the Philippines, Vietnam and Malaysia can demarcate their overlapping Exclusive Economic Zones and extended continental shelves in the Spratlys based on the ruling of the arbitral tribunal that all the high-tide geologic features in the Spratlys generate only territorial seas and generate no exclusive economic zones. This will enforce the arbitral ruling by state practice.

Fourth, the five ASEA member-states can sign a convention declaring the entire Spratlys an international marine protected area since the Spratlys are the spawning grounds of fish in the South China Sea. Without the Spratlys as spawning grounds, the fish stock in the South China Sea will collapse. Only civilian facilities should be allowed in the Spratlys, and the existing military facilities can be converted into marine research or tourism facilities. The convention can be opened for accession by other states. China will be the number one beneficiary of such a convention because China now takes more than 50 percent of the annual fish catch in the South China Sea.

Fifth, the five ASEAN member-states can conduct joint patrols beyond the territorial seas of the high-tide geologic features in the Spratlys. The joint patrols, by navies or coast guard vessels, or both, can enforce international laws and conventions on the environment, marine conservation, biodiversity, and piracy. These joint patrols, an exercise of freedom of navigation, will enforce the arbitral ruling by state practice.

All these multilateral undertakings will promote peace, security and stability in the South China Sea.

On the Code of Conduct, what is paramount is that the Code, if signed, should not legitimize the seizure by China of territorial and maritime areas in the South China Sea. It should not legitimize the artificial island building by China on low-tide features and the severe damage to the marine ecosystem that China’s island building has caused. it should not prevent any of the parties from resorting to the dispute settlement mechanisms under international law, in particular UNCLOS. It should be expressly written in the Code of Conduct, without any ambiguity, that the Code does not supplant or supersede UNCLOS in any way.

The Code of Conduct is not intended to settle the merits of the claims of the disputant states. The Code is intended to manage the conflict to preserve peace and stability in the South China Sea, to prevent the use or threat of force while the merits of the dispute are under negotiation or arbitration. The Code should not be used to legitimize claims or activities that are otherwise illegal under international law. The Code should not be a vehicle to allow China to recover what it had already lost under the arbitral ruling in the South China Sea arbitration at The Hague.

China has declared that it wants the Code of Conduct signed by 2022. In the past, China has always said that it will sign a Code of Conduct at the appropriate time, when the time is ripe. That time, as declared by China now, is sometime in 2022. Why 2022 and not 2019 or 2020?

China has not finished its island building and will reclaim Scarborough Shoal, a high-tide feature, between now and its signing of the Code of Conduct sometime in 2022. China was about to reclaim Scarborough Shoal in early 2016 when it sent dredgers to Scarborough Shoal. The Chinese dredgers were monitored by American satellites. President Obama telephoned President Xi Jinping that the U.S. would take measures if China proceeded with its reclamation of Scarborough Shoal. China backed off. But now we know that China has a plan to reclaim Scarborough Shoal. DND Secretary Delfin Lorenzana has recently confirmed that China was about to start its dredging of Scarborough Shoal in 2016 but was stopped by President Obama.

We know that China is just biding its time. China’s strategic plan to control the South China Sea for economic and military purposes dictates that it must build an air-and-naval base on Scarborough Shoal. China’s radar, anti-ship and anti-aircraft missile and fighter jet coverage of the South China Sea has a loophole in the northeast area of the South China Sea, and an air-and-naval base on Scarborough Shoal will plug this loophole. It is just a matter of time before China makes its move.

The window of opportunity for China to build on Scarborough Shoal is before President Duterte leaves office in June 2022. President Duterte has stated before that there is nothing he can do to stop China if China builds on Scarborough Shoal. This is practically flashing the green light to China to build on Scarborough Shoal. This means that President Duterte will not send the Philippine Navy or Air Force to even show a token resistance if China builds on Scarborough Shoal. There will be no occasion for any armed attack by China on Philippine military vessel or aircraft, and thus no possibility for the Philippines to invoke the Philippine-US Mutual Defense Treaty. China knows that this is the policy of President Duterte but China is not sure if the next Philippine President will adopt the same policy. So, China will have to make its move before the end of President Duterte’s term in June 2022.

After China completes its air-and-naval base on Scarborough Shoal, China will then announce it is ready to sign the Code of Conduct. This means that effective from the signing of the Code of Conduct, no new reclamation or island building can take place within the territorial or maritime areas under dispute in the South China Sea. Unless the Code of Conduct makes an express reservation, this means that all prior reclamations and island building by China will gain de facto recognition by the other disputant states. This is the scenario China considers as the appropriate time to sign a Code of Conduct. This is the scenario that I fear may happen.

Is there a light at the end of the tunnel in the South China Sea dispute? Yes, there is, insofar as the maritime dispute is concerned.

Last November 2018, during President Xi Jinping’s visit to Manila, the Philippines and China signed the MOU on joint cooperation to explore and exploit oil and gas in the West Philippine Sea. The Philippines and China later signed the Terms of Reference or TOR implementing the MOU. Under the MOU and TOR, a designated Chinese commercial enterprise, and CNOOC has subsequently been named for this purpose, will enter into an agreement with a company holding a service contract with the Philippine Government. The agreement may either be for CNOOC to come in as equity holder of the service contractor, or as sub-contractor of the service contractor, or both. In case an area has not been awarded any service contract, the PNOC Exploration Corporation will be the counterpart of CNOOC.

During the visit of President Duterte to Beijing late last month, the Philippines and China named their representatives to the Steering Committee, the government-to-government committee that will oversee implementation of the MOU and TOR. The next step is for members of Working Group to be named, and these should be the representatives of CNOOC and the Philippine service contractor. In Reed Bank, which is the most promising area, that service contractor is Forum Energy, which holds an existing service contract from the Philippine Government.

What is the significance of the MOU, TOR and the activation of the Steering Committee and the Working Group? Under the MOU and TOR, China, through its state-owned commercial enterprise, will participate in energy exploration and development as, or through, a contractor of the Philippine Government. Every service contractor of the Philippine Government, by the nature of its undertaking to provide services and by express stipulation, recognizes that the oil and gas belong to the Philippines, and as service contractor it will be paid a fee for its services in extracting the oil and gas, and the payment will either be in cash or in kind.

Thus, there is an implied admission by China that the oil and gas in Reed Bank and other areas covered by the MOU and TOR belong to the Philippines. Together with the arbitral ruling, this should be sufficient to preserve and protect our exclusive sovereign rights in the West Philippine Sea. We cannot expect China to admit expressly in writing that the Philippines has exclusive sovereign rights in the West Philippine Sea. The Chinese Government will have to justify the MOU and TOR with the Chinese people, and we must help the Chinese Government find a face-saving solution.

But we must be firm that any cooperation on oil and gas in the West Philippine Sea must follow the structure under the MOU and TOR. There should be no deviation whatsoever from the MOU and TOR.

I understand that the core elements of the MOU and TOR can also form the basis of similar agreements between China and the other ASEAN disputant states. If so, then we would have found the formula, under the Duterte Administration, for a South China Sea-wide peaceful settlement of what is considered as the most intractable maritime dispute in the world today.

Thank you and a good day to everyone.