Disinformation innovations used in the May 2019 Philippine elections

Three months after the May 2019 elections, the Social Weather Stations (SWS) survey results showed 80 percent were satisfied with the conduct of the elections. Two reports from Rappler Plus, and Jonathan Corpuz Ong, Ross Tapsell and Nicole Curato researched more on the use of digital technologies and social media in Philippine politics and electoral campaigns. Rappler Plus dealt with Social Media, Disinformation, and the 2019 Philippine Elections, the copy of which is available to members. Ong et al. studied Tracking Digital Disinformation in the 2019 Philippine Midterm Election.

Being active in social media platforms since 2007, I observed that strategies have evolved since 2010, when social media was first adopted by candidates in the 2010 Philippine national and local elections. The Ong, et al. report confirms my observations and first-hand experiences in the May 2019 elections.

The report of Ong, et al. offered three key messages. Their first pertains to social media and disinformation becoming more central and entrenched in the conduct of Philippine political campaigns. The second message is that disinformation producers are becoming more insidious and evasive. The third key message is that existing regulatory interventions are not adequate, since disinformation industry has become increasingly well-funded and harder to detect.

Ong, et al. added that “social media alone cannot swing a whole election, their effects are profound: they could bait and divert public attention, normalize public incivilities, and mobilise communities through hyper-emotional and partisan communication that makes listening across difference impossible.” Disinformation innovations in the 2019 elections reveals a shift from the ones used in the 2016 elections.

From online celebrities to micro-influencers

Disinformation got more insidious as the campaign shifted from the use of online celebrities to micro- and nano-influencers. Digital strategists used the rise of micro- and nano-influencers to gain more engagement, trust and authenticity. Influencers from political parody accounts, Pnoy pop culture accounts and thirst trap Instagrammers cultivate intimate and interactive relationships with their followers. When a post on politics come from them, it would appear organic, sincere and more compelling. Bloggers pointed me out to Instagram accounts that published photos of a 95-year-old political candidate among their usual content of shirtless, gym gains and lifestyle selfies. Nothing wrong with taking part in such campaigns but none of the thirst trap Instagrammers disclosed #PaidAd, or a sponsored ad in their posts. Campaign spending got tougher to monitor after the campaign season, since many micro-influencers took down posts with political content. Political propaganda tracked by Rappler Plus were found in pages whose content are not as directly associated with political messaging such as those that usually share memes and viral content and even buy-and-sell pages.

From clickbaits to communities

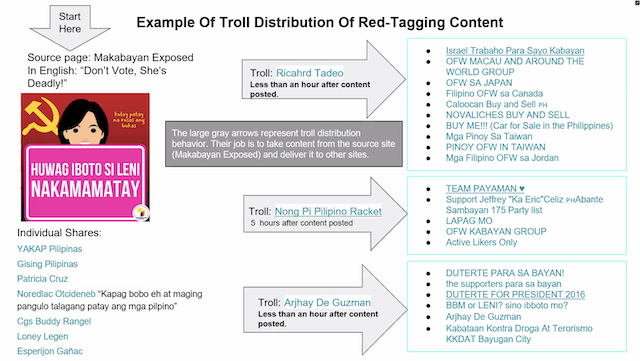

A closed Facebook group that I followed because of my academic background shared hyper-partisan content. Individuals who argued with pro-Duterte members were harassed with homophobic slurs. The power in this group lies in administrators, who could grant access to members and protect the group from outsiders. Closed groups target overseas Filipino workers (OFW) and conspiracy groups like the Filipino Flat Earth group. Coordinated behavior in Facebook was also observed by Rappler Plus. Candidate official pages and support linked directly and indirectly, showing that they either amplified each other or amplified the same messages or content.

A digital strategist delivers two approaches in these communities. One tactic is to use disinformation in a more subtle and discreet way. For example, the use of OFW groups is powerful. Another is a partisan approach which is the Facebook group I belonged to. Some use both approaches at the same time.

From peripheral to central

Digital underground operations have become part of campaign strategies which is not limited to Manila and Luzon, but reaches out to urban centers in Visayas and Mindanao. It also operates from the national to local even to village-level elections. The mainstreaming of disinformation strategies create an industry of ragtag operations who employ young digital workers often in precarious work arrangements. Campaign teams dictate the content to micro media managers who then engage in troll farming. Those hired in the project, copy and paste content in comment sections. Jose Mari Lanuza in an Aug. 11, 2019 TV interview with Karen Davila revealed the amount of “copy paste” work at 500 pesos a day in provinces to 1000 pesos a day in Metro Manila.

Whether or not you were satisfied with the May 2019 elections, find out if your beliefs are affirmed by posts in your closed groups and your timeline. The problem with people believing disinformation is that, even when confronted with truth/facts, they tend to dig their heels in. Perhaps, we are also victims of our own echo chambers.

Interventions are needed in the light of disinformation innovations. Rappler Plus suggests that social media platforms need to be committed in arriving at solutions. One needs to address false information used to manipulate public opinion about candidates and the process and anonymously managed pages and fake accounts that circulate this propaganda content.

I am not in favor of censorship or additional legislation to curb disinformation. Whose discourse are we allowing anyway? We have enough laws to address the problem of disinformation or fake news, Republic Act 10951, the Revised Penal Code and the Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012 being the most obvious examples. What we need is fair and just enforcement.

Ong et al. recommends a “process-oriented responses that uphold virtues of transparency, accountability and fairness in the conduct of political campaigns and decision-making on social media regulation.” Instead of taking down speech and content, a call for more transparency initiatives, including collaboration with fact checkers, journalists, civil society and academics is needed.

Tracking digital disinformation in the 2019 Philippine Midterm Election by Ong Tapsell and Curato (2019). Public report available at: www.newmandala. org/disinformation

First publsihed at Sunday Business & IT on August 18, 2019.