Aid Monitoring: Citizens’ Initial Efforts in the Wake of Typhoon Yolanda

On the trail of Yolanda’s Billions

by Noemi Lardizabal-Dado, Jane T. Uymatiao and Carlos Maningat

(This article is Blog Watch’s final investigative reporting project for Data Journalism PH 2015, a training program for journalists and citizen media, under the auspices of the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism, in partnership with Open Knowledge Foundation.)

Super Typhoon Haiyan (locally called Yolanda) barreled into the Philippines on November 8, 2013. A Category 5 typhoon, it wrought massive devastation on the country’s eastern seaboard, with thousands of lives lost, properties flattened, hundreds of thousands rendered homeless, and businesses wiped out.

In its aftermath, the Philippines saw the generosity of the world. Donations in cash and kind soon poured in. Yet with so much money being pledged and sent to the country, Blog Watch noted that there was no formal reporting or monitoring infrastructure to record financial donations or pledges.

A citizen-initiated aid monitoring tool was created

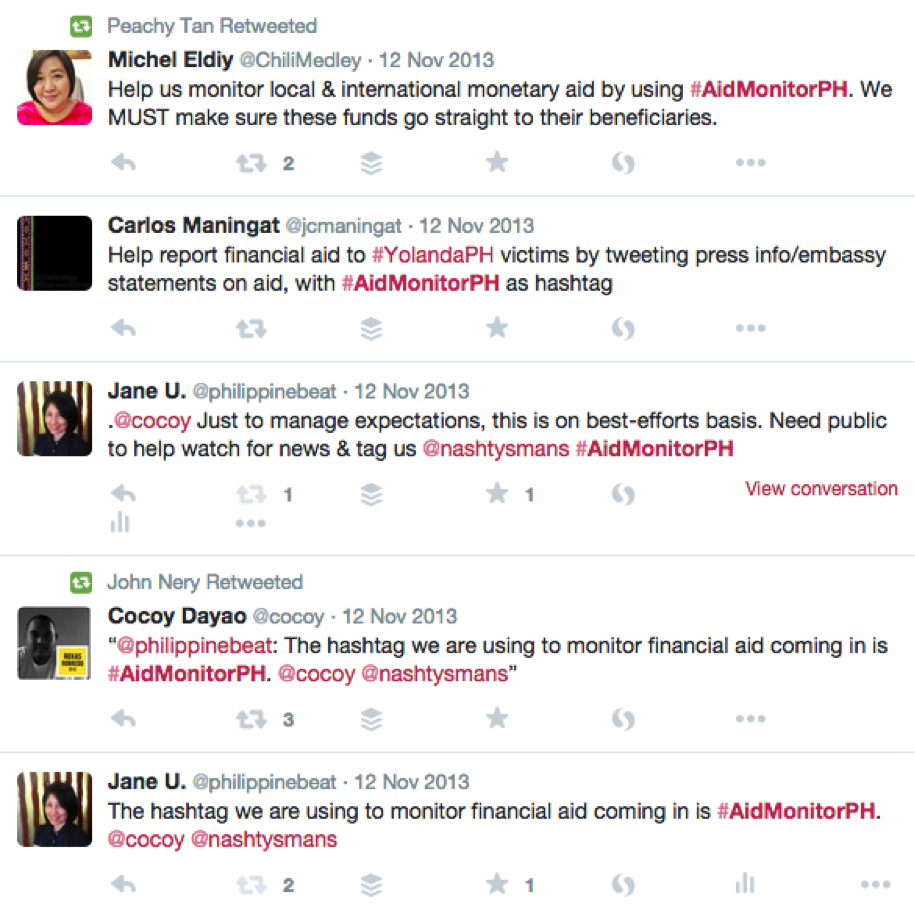

Blog Watch decided to harness the power of crowdsourcing for donation information and aggregate the amounts. On November 12, 2013, just four days after Yolanda (Haiyan) hit, it put up the hashtag #AidMonitorPH. The hashtag was immediately adopted by netizens and some media organizations, with people using it to tag any and all mention in news articles about donations.

READ: How citizens are tracking #YolandaPH foreign financial aid via #AidMonitorPH

By the afternoon of November 12, 2013, Blog Watch had come up with a very rough spreadsheet on Google Docs that it named Yolanda Aid Monitor. Netizen friends and other social media people began helping out, using the #AidMonitorPH hashtag together with links to articles about donations.

The Yolanda Aid Monitor initially began as an alphabetical listing of donor individuals, groups, companies, and institutions (foreign and local) based on published data (articles, social media). Eventually, as the list grew longer, categories were added so donors could be classified into Corporations, Foreign Governments, International Groups, Local Governments, Private Foundations, and Individuals.

Blog Watch, being an informal group of citizen advocates, had no direct access to the donors; neither did it have the resources to validate the amounts. But that did not deter us from trying to establish the magnitude of donations. Published articles by media were our first sources. We validated the donations and amounts in two ways: 1) checking donor websites (if any) for mention of the donations; and 2) searching in donors’ social media accounts or websites for any mention of the donations to confirm news reports.

The beginnings of government’s transparency hub

On November 18, 2013, the government launched its own Foreign Aid Transparency Hub (FAiTH). The site described its content as “all aid (pledged and received) from foreign countries, multilateral organizations, NGOs, private individuals and anonymous donors.”

Based on the FAiTH data, the government had received P17.23 billion in foreign aid out of the P73.307 billion pledged by foreign donors, or 23.5 percent of the total Yolanda aid pledged. But the listing of amounts received had no breakdown per sector/ rehabilitation project, thus making traceability of funds very difficult. In other words, there was a blind spot: a gap in the reporting that excluded donations channeled from foreign donors to nongovernment institutions (NGOs), local government units (LGUs) affected, private relief agencies, or even directly to individuals/families.

From FAiTH to eMPATHY

FAiTH was maintained as the government hub to keep track of donations received and pledged until an Office of the Presidential Assistance for Rehabilitation and Recovery (OPARR) headed by Panfilo Lacson was established. The data of FAiTH were then moved to another website called Electronic Monitoring Platform Accountability and Transparency Hub for Yolanda(or eMPATHY). This time, the ability to input data was opened up to the donor entities themselves as each one had its own username and password to do so.

eMPATHY allowed one to zoom in on specific project lists by category, by province, and by city/ municipality. The portal also allowed users to generate custom Excel tables based on selected filters and subcategories, making it more useful than FAiTH.

But while using eMPATHY was easy, it did not show the amount of actual funds disbursed and the status of projects.

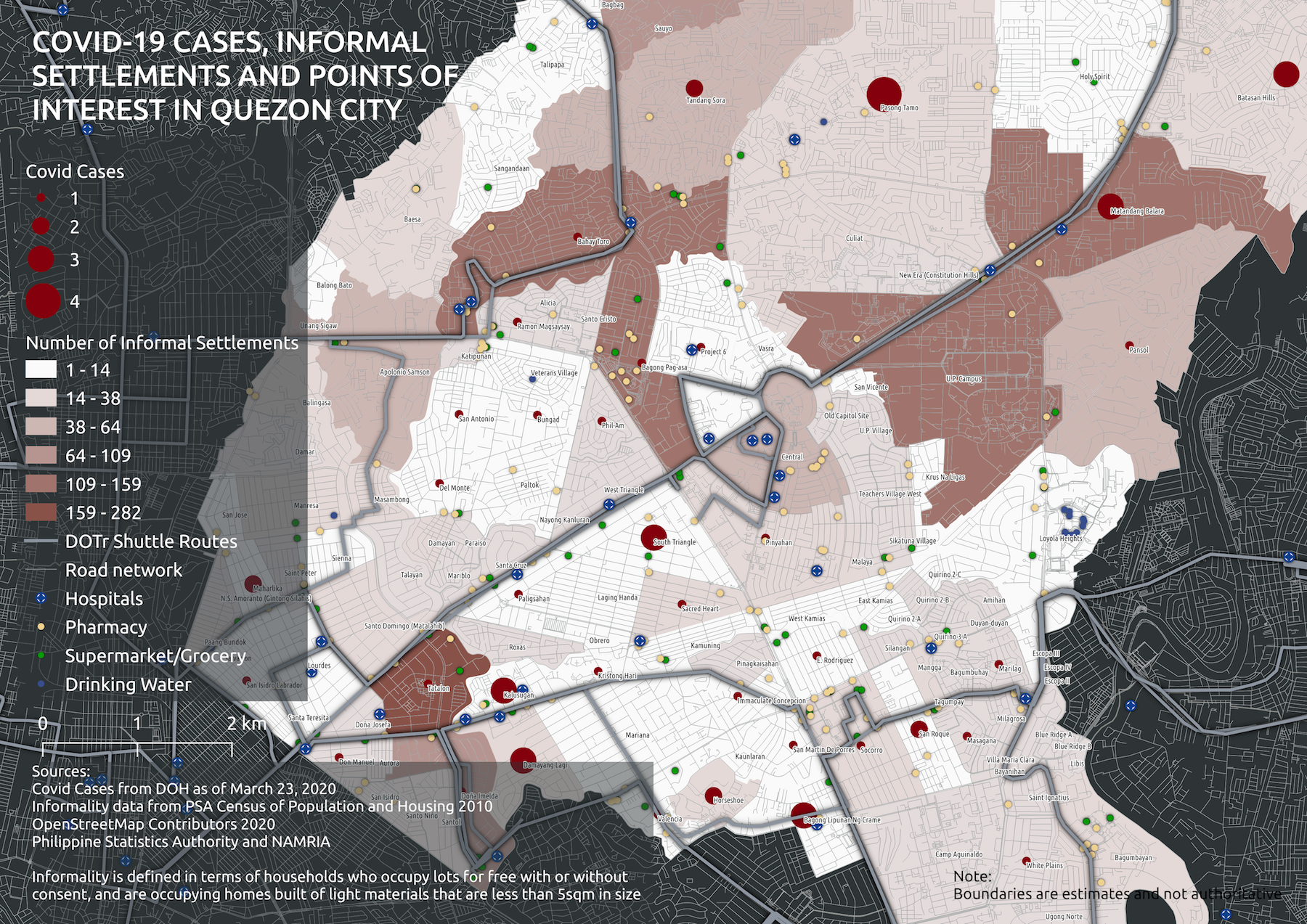

A focus on Tacloban City and Guiuan

source: Social Watch Philippines, April 28, 2015

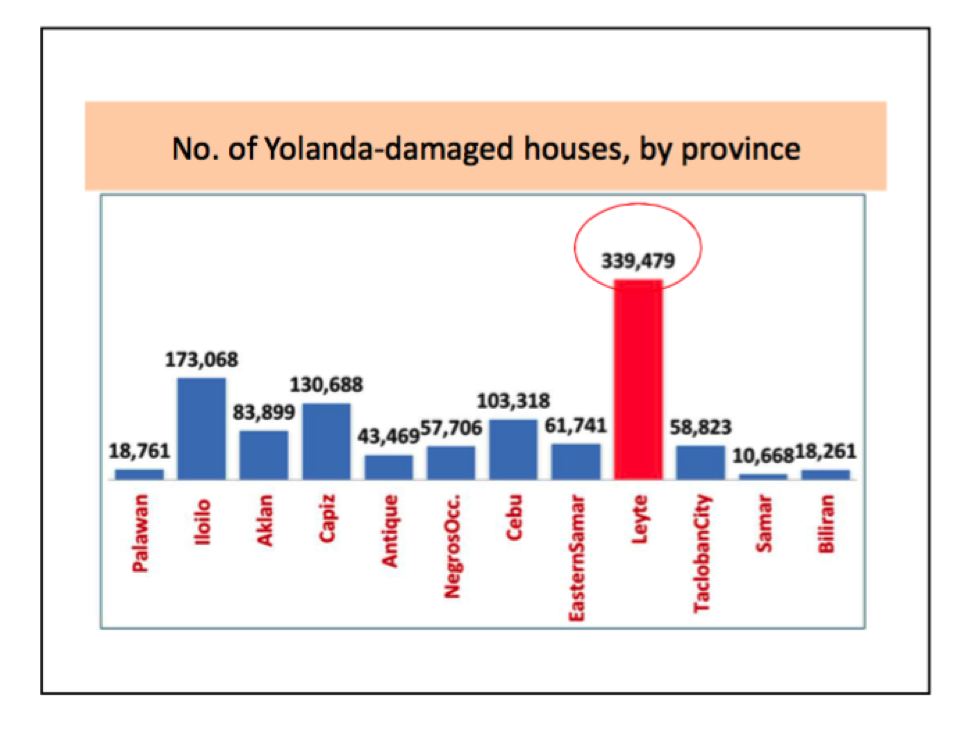

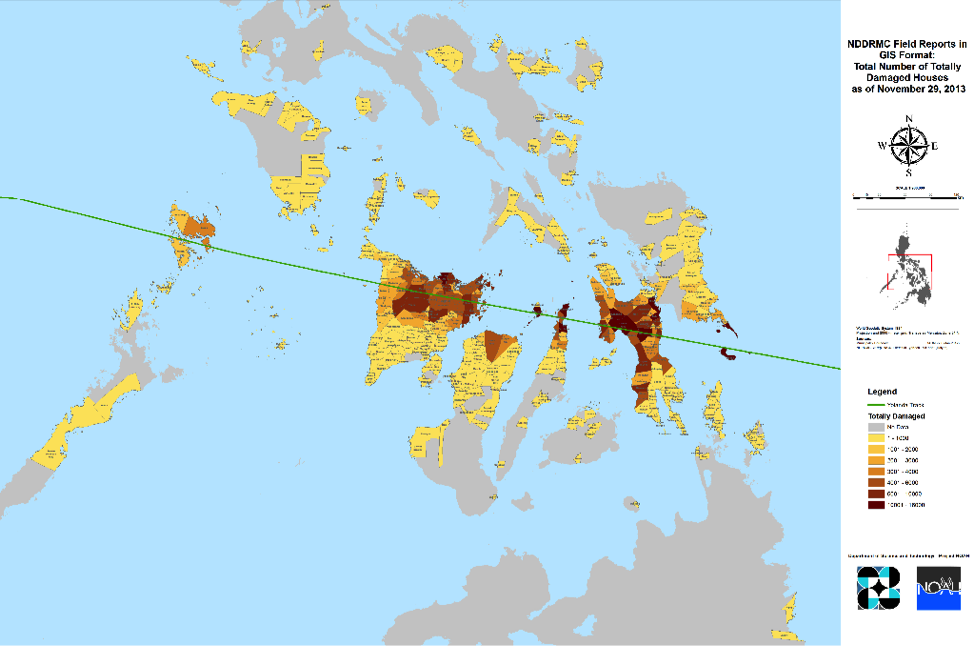

Social Watch Philippines Inc. (SWP) said that based on data culled by the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) in 2014, the biggest damage was in Region 8 with 99.9 percent of the barangays affected, which could be broken down into 550,880 families and 4,271,726 persons . The number of Yolanda-damaged houses in Leyte, meanwhile, reached 339,479; Tacloban City 58,823; Eastern Samar 61,741 ; Samar 10,688; and Biliran 18,261. The National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC) field reports in geographic information system (GIS) revealed similar figures, placing the total number of damaged houses (partially and totally) in Tacloban City at 58,823, while 12,270 homes were totally damaged. Totally damaged homes in Guiuan reached 10,008 — almost as much as Tacloban, according to the reports.

NDRRMC Field Reports in geographic information system( GIS) Format as of 29 November 2013 GIS map showing the number of totally damaged houses per city or municipality: Bogo City (15,824), Daanbantayan (15,660), Palo (15,481), Ormoc City (14,132), Roxas City (13,590), Bantayan (12,333), Tacloban City (12,270), Kananga (11,695), Burauen (10,800) and Guiuan (10,008).

We decided to limit the scope of our study to the top two priority areas in Region 8, namely Tacloban City, Leyte and Guiuan, Eastern Samar, based on the prioritization ranking scores from the Humanitarian Response . The scores made use of population data and poverty data from the National Statistics Office and the data on affected persons and damaged houses from Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) as of December 11, 2013. The modelprovided a Total Priority Ranking based on the following indexes: affected persons (25 percent), totally damaged houses (35 percent), partially damaged houses (15 percent) and poverty index (25 percent) . The priority ranking score for Guiuan was 7.4 while Tacloban City was 7.2 , placing these two within the top three priority areas before rehabilitation started. The prioritization ranking was the initial assessment of the Humanitarian Response and “should be valid for approximately the first month, but should align with assessment efforts. “

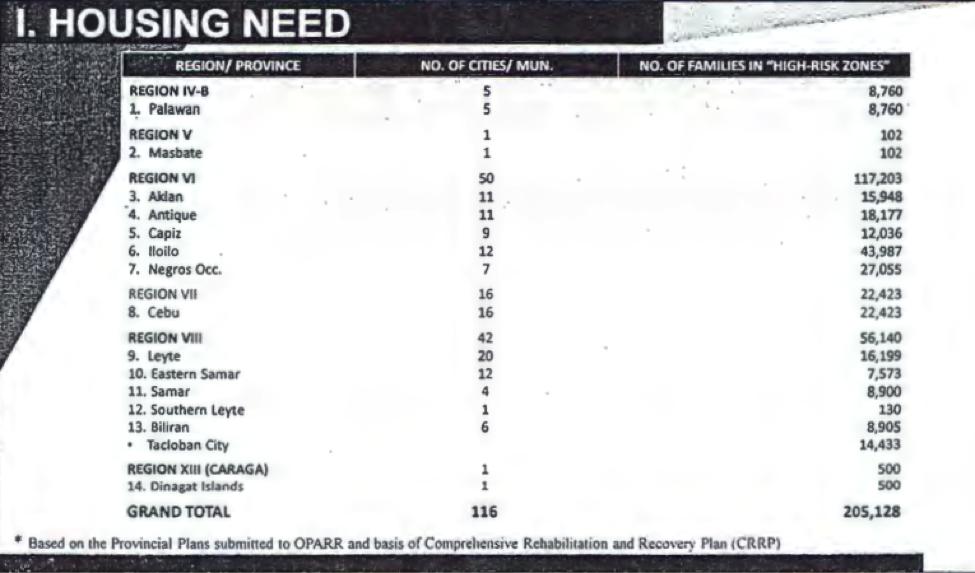

With over one million homes that were in or along Yolanda’s path either destroyed or damaged, the issue of resettlement of the supertyphoon’s victims became a serious concern.

Using the data from eMPATHY and from the National Housing Authority (NHA), Blog Watch assembled data on resettlement projects in Tacloban City and Guiuan based on progress update, area covered, housing units built compared to targets, and actual number of beneficiaries.

So far, Blog Watch has extracted the following data from eMPATHY and assembled these into a table: resettlement projects in Tacloban City, barangay-specific location, project cost, amount disbursed (mostly unavailable), funding agency and project status (unavailable). From this data, we generated an estimate of the cost per housing unit for each of the resettlement projects in Tacloban City.

Based on the available data, the most common cost per housing unit is P292,900 – which is actually higher than the government’s maximum allocation of P290,000/ housing unit. There is one project wherein a housing unit cost only P36,319, while one project by Habitat for Humanity has housing units pegged at a whopping P1.4 million each.

Comparison of cost per housing unit, select Tacloban resettlement projects

Source of basic data: NHA, eMPATHY

We also found out that there is only one resettlement project in Guiuan (in Brgy. Tagpuro) despite being one of the most heavily devastated areas by super typhoon Yolanda. Based on the data from the NDRRMC, over 10,000 homes were totally damaged in Guiuan, a figure that approximates the 12,270 totally damaged homes in Tacloban City.

Only 44% of Yolanda houses targeted for Tacloban City are up

The government has completed only 44 percent of its target housing units for the victims of super typhoon Yolanda in Tacloban City two years after the deadly disaster, based on NHA and NEDA data.

Of the 14,388 permanent houses targeted for Tacloban City, only 5,821 housing units have been “substantially completed” while only 534 units were completed. Of the total target housing figure, 2,227 were built in the village of San Isidro. No data have yet been provided regarding the number of resettlement beneficiaries.

A very important statistic came up in the course of the group’s data gathering: the number of housing units completed so far in Tacloban City is less than one percent of the 58,823 houses heavily damaged by Yolanda.

In Guiuan, the resettlement effort is even more dismal as only 212 homes were substantially completed out of the 10,008 homes totally damaged (2.11 percent), while 659 housing units are still under construction in the villages in Tagporo and Sapao. These data were based on NHA’s reply to an inquiry by Sen. Joseph Victor ??JV’ Ejercito as of August 25, 2015.

Overall, the government has completed only eight percent (16,544 units), or less than 1 out of 10, of the target 205,128 housing units in six regions devastated by Yolanda with 72,738 housing units still under construction. This was revealed by NHA General Manager Sinfroso Pagunsan during a Senate hearing last October 6.

Pagunsan said around 45,000 housing units are expected to be completed by the end of 2015.

Rhoda Avila, Rights in Crisis Policy and Campaigns Officer of Oxfam Philippines, said the delays in construction can be attributed to the time-consuming finalization of hazard maps in Yolanda-affected areas.

Avila said the hazard area classification is mandated under the Joint Memorandum Circular 2014-01 among the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG), Department of Science and Technology (DOST), Department of National Defense (DND), and the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH). The joint memorandum circular was signed Nov. 5, 2014 or a year after the disaster.

Explaining that different agencies had to come up with hazard-specific maps, Avila told Blog Watch: “Tinapos kasi ang mga hazard maps. Hindi sila [LGUs] kikilos agad kapag hindi pa readyang hazard map. Yung iba’t ibang mapa kasi, in-overlay ??yun. It took some time siyempre(The hazard maps were finished first. They wouldn’t do anything until the hazard maps were ready. Different maps had to be overlaid. They thus took some time (to complete).”

For instance, Avila said, the Mines and Geosciences Bureau (MGB) focused on the mapping of landslide-prone areas while Project NOAH focused on mapping flood-prone areas.

Aside from the finalization of the hazard maps, Avila said the LGUs had difficulty finding public lands for the resettlement of Yolanda victims.

“Nahirapang humanap ng public land ang mga LGUs (The LGUs had a hard time looking for public land),” she said. “Kung walang makitang public land halimbawa, kailangan bibili ng lupa ang LGU. Dapat clean ang title. (For example, if a piece of public land cannot be found, the LGU has to buy land. The title has to be clean.)”

Painfully wide gaps between planned and actual housing projects

In the two years that have passed since Yolanda struck the Visayas, the housing gaps remain too large, with progress nowhere near the halfway mark.

Source: National Housing Authority, September 2015

There is a big data gap between the actual number of damaged houses and the number of targeted/actual housing reconstruction set by the government in both Guiuan and Tacloban City. The gap, however, is wider in Guiuan.

SWP co-convenor Isagani Serrano remarked, “When Yolanda struck in 2013, we saw an unprecedented demonstration of heroism and basic humanity in humanitarian response. Government efforts were ably supported backed by complementary efforts from nongovernment organizations and the private sector. Considering the positive start government can build on, it’s hard to justify the pathetic progress in rehabilitation and reconstruction. We are not building back better; we are not even building back to pre-Yolanda situation which was a picture of risks and vulnerabilities to being with.”

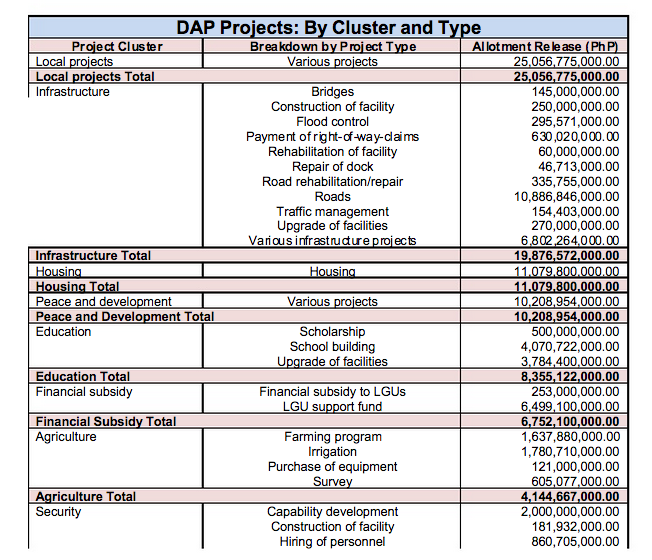

The Yolanda Comprehensive Rehabilitation and Recovery Plan (CRRP) had envisioned the “PhP167.9-billion funding requirement to rebuild the affected areas until 2016. It’s a whopping figure, yet coming up with the needed money seems to be surprisingly easy.”

According to a PCIJ report , “some 58 foreign governments and the European Commission alone have already given some PhP29.84 billion or US$ 667.5 million as of October 2014, according to donor documents. Combined with the total releases from the public coffers for Yolanda as of November 2014, the funds and donations add up to PhP81.89 billion in all.”

SWP, for its part, looked at the PhP167 billion committed by President Benigno S. Aquino III for Yolanda rehabilitation. In an interview, SWP lead convenor Leonor Magtolis Briones said, “Our research study is on the utilization of public funds for Yolanda. We did not include the foreign donors because they have their own systems of accountability which are very strict. “

SWP said that the emergency shelter assistance (ESA) was received by Yolanda victims more than a year after they lost their houses. In fact, the bulk of funds for ESA was downloaded to local government units only in June this year and received by its intended beneficiaries only recently. The people interviewed by SWP in the provinces covered by its study also raised several complaints about unclear guidelines on ESA that left out other equally poor households in need of having their houses repaired or restored. SWP noted as well, “Majority of those living in areas declared unsafe zones are still living in bunk houses, transitional shelter or are back to their houses in unsafe zones. Delay in recovery efforts is unjustifiable and the people demand for immediate government action to address the problems.”

It also noted that while construction for permanent housing started in most Yolanda-affected areas, setbacks such as land acquisition, pricing, resistance by target beneficiaries, and documentation were encountered.

In certain local government units (LGUs), the land acquisition problem is that there are no titles; “owners” only have tax declarations. This contributes to the inability to identify “safe areas” for permanent housing. Moreover, according to the SWP presentation made available to Blog Watch, “some LGU officials want to grab credit for delivered Yolanda-benefits, e.g. in the distribution of ESA where the Congressman and the Vice- Governor appear to not want the presence of one or the other.”

SWP added that “some LGU officials intervene in the distribution of ESA (i.e., want to reduce the P30k-ESA for beneficiaries with totally damaged houses to P22.5k) and the difference be given to more families/beneficiaries of the P10k-ESA for beneficiaries with partially damaged houses.”

Conclusion and Recommendations

Based on Blog Watch’s initial attempts to monitor aid, our understanding of what FAiTH and eMPATHY sites contained, and from all other information gathered on the state of housing rehabilitation, several conclusions and recommendations can be made:

- There should be a PERMANENT reporting infrastructure that would automatically record, track, and monitor inflows and outflows of foreign and local donations after every disaster. FAiTH and eMPATHY tried to fill this role but from their information and the site name (eMPATHY was specifically for Yolanda only), it is clear that the sites were only created in direct response to citizen calls for transparency and accountability. They were not institutionalized reporting frameworks.

Recommendation: The eMPATHY portal is a good start. However, it should not be used for Typhoon Yolanda efforts alone. It should be expanded and institutionalized so that all future disasters (typhoons, earthquakes, and other catastrophes) will have their own micro sites within the portal. In addition, information on actual funds disbursed, what rehabilitation projects they are for, and continuing status updates on such projects, should be added to the portal.

- There is no central agency or body with a clear mandate and budget to lead, supervise, and coordinate government efforts in disaster preparedness and response, reconstruction, and adaptation and mitigation of risks to prevent a disaster. This central agency concept was also suggested by Prof. Briones for the immediate resolution of the snags in the implementation of the reconstruction plan. Panfilo Lacson, head of the now defunct OPARR, also recommended that a “permanent agency should be equipped to handle all functions related to preparedness, recovery, and rehabilitation since we are a typhoon-prone country.”

Recommendation: More frequent, high impact disasters are the new normal in the Philippines. The government has to seriously consider setting up this central agency for complete transparency and clear accountability from disaster preparedness to rehabilitation. NDRRMC is a start, but it is focused on monitoring and rescue. It does not have a proactive preparedness program (reason why disaster preparedness initiatives like Project Agos prosper) or a robust infrastructure for post-disaster rehabilitation. An umbrella agency tasked to cover disaster preparedness all the way to mitigation and rehabilitation, as well as accountability for donations, can cover all bases.