Maguindanao Massacre, Year 4: 23 journalists killed in 40 months of PNoy, worst case load since ‘86

By the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

First of Two Parts

HIS MOTHER is a former president who was widowed when her husband, a prominent opposition leader, was assassinated. And so when Benigno Simeon ‘Noynoy’ C. Aquino III came to power on June 30, 2010, expectations were high that he would act with dispatch and resolve on the unsolved murders of activists, lawyers, church workers, and journalists.

Aquino himself promised as much – and more. In his first State of the Nation Address or SONA, he vowed that his administration would work to end the reign of impunity and extrajudicial killings. In its stead, Aquino said, his administration would usher in an era of “swift justice.”

“Kapayapaan at katahimikan po ang pundasyon ng kaunlaran (Peace and order are the foundations of progress),” Aquino said in his first SONA. “Habang nagpapapatuloy ang barilan, patuloy din ang pagkakagapos natin sa kahirapan (So long as there is gunfire, so too will we continue to be impoverished).”

Aquino did busy himself trying to address the country’s economic woes. In the first half of his term, Aquino and his economic managers assiduously sought and in time earned the Philippines unanimous upgrades from the world’s most creditable ratings agencies, notably Fitch, Moody’s, Standard & Poor.

Parallel to that, however, were the country’s lower and lower scores from the world’s most creditable human rights monitoring agencies – in large measure because of the rising numbers of media murders, and the slow, tepid results of official action on the cases.

Under Aquino, the Philippines has scored steadily dipping ratings in recent years from international groups monitoring the state of human rights, media freedom, and freedom of expression such as the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), Amnesty International, Reporters Without Borders, Freedom House, Human Rights Asia, and the Southeast Asian Press Alliance.

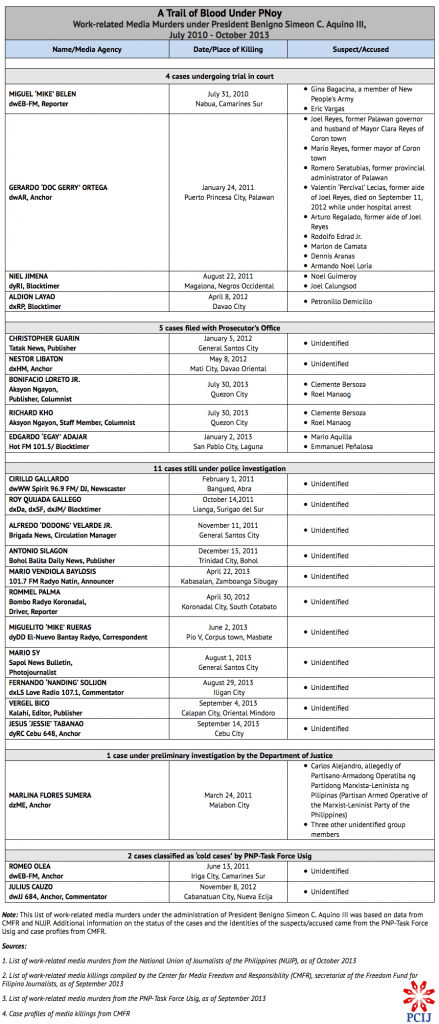

In fact, during Aquino’s first 40 months in office, from July 2010 to October 2013, at least 23 journalists were killed, among them 16 radio broadcasters and seven print journalists. It is a trail of blood redder, thicker, and worse compared to the number of work-related media murders per year under four other presidents before him, including his late mother Corazon ‘Cory’ C. Aquino and his immediate predecessor Gloria Macapagal Arroyo.

Only 4 cases in court

Of these 23 media-killing cases, half are already dead in the water because of failure by police investigators to identify or arrest suspects. Only four are in the trial stage. Twelve of the murder cases have no charges filed against anyone yet, while the remaining seven are still in the level of the public prosecutor or the Department of Justice (DOJ) for the determination of probable cause. In other words, less than a fifth of the media murder cases have moved beyond the investigation phase.

For sure, part of the problem lies with a criminal justice system that is in need of a serious overhaul. But there is also no doubt that for so long as the Aquino administration continues to lack clear and unequivocal policy directions on media killings, the trail of blood will only get longer.

“The killings are being encouraged by the fact that of the killers of journalists, no mastermind has been tried or punished,” says former University of the Philippines College of Mass Communications Dean Luis Teodoro, now a trustee of the Freedom Fund for Filipino Journalists (FFFJ).

“What is disappointing is that we were hoping (for better) under President Aquino, son of the two icons of democracy,” says Rowena Paraan, chairperson of the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP).

“He ran under a platform of anticorruption, transparency, and human rights,” she says. “We were thinking na magkakaroon ng political will and decisive action to address the killings, not only of the media, but also of the activists, priests, and lawyers.”

For this report, PCIJ reviewed the records of two independent media agencies that have been monitoring media murders in the country since 1986: the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility (CMFR) and NUJP.

CMFR is the secretariat of FFFJ, which is composed of the Philippine Press Institute (PPI), the Kapisanan ng mga Brodkaster sa Pilipinas (KBP), CMFR, and PCIJ.

Under Aquino, CMFR has documented 19 media murders, while NUJP has monitored 18. Fourteen cases appear in both lists. CMFR’s list, however, has five cases not enrolled in NUJP’s records, while NUJP has four cases not appearing in CMFR’s list, hence PCIJ’s total count of 23 cases of media murders.

Aquino had actually started his term on a relatively high note with media groups. Just months before his election as President, Aquino had pledged to support the long-delayed Freedom of Information (FOI) bill, drawing cheers from media organizations.

Appeals for urgent action

Two months into his presidency, in August 2010, Aquino agreed to meet with FFFJ and NUJP to discuss the groups’ concerns about the spate of media killings, which had peaked during the time of his predecessor and nemesis, Gloria Macapagal Arroyo.

But Aquino skipped the scheduled meeting on account supposedly of more pressing matters. It was to be a portent of the President’s apparent lukewarm attitude toward the cases.

The meeting was held just the same in Malacañang, with Justice Secretary Leila de Lima, and Communication Secretaries Herminio Coloma Jr. and Ricky Carandang and Undersecretary Manuel Quezon III in attendance. They received from FFFJ and NUJP full documentation of all the cases of media murders since 1986, and a list of matters requiring “urgent action” by the President.

FFFJ and NUJP implored the Palace to act with dispatch on, among others, the service of arrest warrants that local courts had issued months earlier against the masterminds and suspects in at least two media murders.

The officials and journalists agreed on concrete steps that could be taken, such as the formation of police tracker teams to locate suspects, the possible creation of special courts to assure swift and continuing trial of cases, and the conduct of dialogues with local officials and citizens in “high-risk areas” where state and non-state actors hostile to independent media abound.

The meeting also focused on several concerns that FFFJ and NUJP noted stand in the way of the litigation of cases, including:

- The dire need to upgrade the training and capability of police investigators assigned to gather evidence, process witnesses, and build cases against both gunmen and masterminds;

- The need to ease the case load of public prosecutors assigned to prosecute media murder cases in court;

- The need to strengthen the Witness Protection Program (WPP) to encourage more witnesses to come forward and testify against the perpetrators; and

- The need for the President himself to demonstrate political will and declare a clear and unequivocal policy to promote and protect press freedom, and to abate cases of harassment and murder of media workers.

Aquino vis Arroyo

These would be recurring themes in succeeding meetings and dialogues between media groups and the Justice Department. In the succeeding months, however, the number of media murder victims began growing again, and would in three years exceed the number of media deaths recorded in the first 40 months of the preceding Arroyo administration.

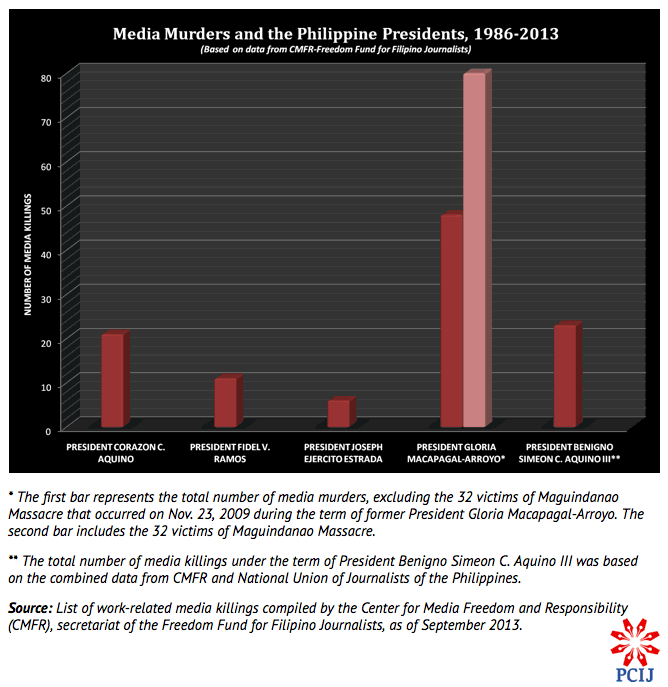

There were 12 media murders, or half the number under Aquino’s, in the first 40 months of Arroyo’s administration, from January 2001 to May 2004.

Viewed from another lens, there are now more journalists killed per year on average under Aquino than there were under President Arroyo or any other Philippine president for that matter – at least if one does not count the monstrous Maguindanao Massacre where 32 journalists were among those killed in a single act of violence in 2009. Including those killed in that tragedy, Arroyo comes out on top, with 80 journalists killed under her watch.

Indeed, the Maguindanao Massacre is regarded as the single worst case of violence against media in the world. But it is often excluded by similar studies in the computations of the average because it is considered sui generis, an outlier or extreme case that would distort the averaging.

Thus, if one were to exclude those killed in the Maguindanao Massacre, there were 48 media victims during the nine years under Arroyo, for a yearly average of 5.05 media murders. In comparison, the 23 media murders under Aquino make for an average of 6.9 cases a year.

‘Extremely distressing’

For further comparison, there were 21 work-related media killings during the term of Aquino’s mother, Cory Aquino, 11 media murders during the six years of President Fidel V. Ramos, and six media murders during the three-year reign of Joseph ‘Erap’ Estrada.

“I think this is extremely distressing,” says Teodoro. “It is developing into a very bad record. (Aquino) has been in power for only three years, and he is already ahead of President Arroyo.”

He also points to another alarming detail: the killings are “coming closer to Metro Manila.”

At least three journalists have already been killed in the National Capital Region, all of them during Aquino’s term: radio journalist Marlina Sumera who was shot dead in Malabon on March 24, 2011; and tabloid columnists Bonifacio Loreto Jr. and Richard Kho who were both killed in Quezon City on July 30, 2013. Prior to their deaths, the murders of journalists had been occurring only in the countryside.

“This is cause for concern,” says Teodoro. “For one thing, the fact that more journalists are getting killed in Metro Manila indicates that the killers of journalists are getting bolder.”

“Previously,” he says, “they thought that if you kill someone in Manila, the possibility that you will be punished is more likely. Now, they are saying that even if you kill someone in Metro Manila, you won’t be punished.”

In 2010, the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) had sounded alarm bells because the country’s ranking that year climbed three notches higher in the list of countries that are fatal to journalists.

No. 3 in impunity list

According to CPJ’s monitoring, from 6th place in 2008, the Philippines soared to number three of 12 countries dangerous for journalists in 2010. Since then, the country has been ranked third in the Global Impunity Index. The country was included each year in the Global Impunity Index together with countries with long records of deadly, anti-press violence such as Iraq, Sri Lanka, Mexico, and Afghanistan.

“Despite President Benigno Aquino III’s vow to reverse impunity in journalist murders, the Philippines ranked third worst worldwide for the fourth consecutive year,” CPJ’s May 2013 statement reads. “Fifty-five journalists’ murders have gone unsolved in the past decade.”

But Presidential Spokesman Herminio Coloma Jr. disputes the rising figures, saying that government investigators had excluded some of the cases from the list of media victims because of questions over whether the killings were work-related or not.

“Task Force Usig pointed out that of so many media killings, it is possible to isolate only a few that truly involve bona fide media practitioners,” Coloma says, referring to the state superbody tasked with dealing particularly with killings of journalists and activists.

Coloma says that some of the media killing cases listed in the databases of local media groups appear to be unrelated to media work. He cites the case of Loreto and Kho, both of whom were columnists of the tabloid Aksyon Ngayon, which had closed before the two were murdered.

“(They) were killed in a drinking spree in Commonwealth, Quezon City, and it was reported right away that these two were journalists,” says Coloma. “Upon closer investigation, their tabloid only had one or two issues before it went out of (circulation). There is nothing about freedom of expression in the crime that was committed, yet in the reportage, it was bandied about that two journalists got killed.”

“We recognize that even if a person is not a media person, the state still has the duty to protect the citizenry,” says the Presidential Spokesman. “But this is just to point out that in the context of the discussions, we need to clarify that number of so-called media killings.”

Justice Undersecretary Francisco Baraan III, head of the DOJ team that investigates and prosecutes media murders, also dismisses the rising media-murder figures. Baraan stresses that Aquino has shown he will not tolerate media killings, and has in fact put in place mechanisms that would address the problem.

“If the cases are going up, it is not because of toleration,” Baraan says. “If there is any president who has been very vocal in statements with respect to human rights violations, it is this president.”

“There is no room in this administration for that,” he adds. “The number does not mean anything as far as this administration is concerned. We cannot make the conclusion that there is toleration or an unwritten policy to go after media practitioners.”

Baraan also raises the possibility that some of the murders may be related to the previous Arroyo administration. He says, “We do not know if these incidents are related to the events in the past, before the administration of this President.”

PNoy and the media

But it certainly is no help that Aquino has shown himself to have little patience or tolerance toward the media. To a degree, he has also shown himself to be unfamiliar, even disagreeable, with the role of a free press. This has manifested itself publicly several times in the last three years, with the President, on occasion, using media events to criticize the way it criticizes his administration.

For example, in April 2012, during an annual conference by the Philippine Press Institute, the country’s association of newspaper publishers, Aquino lashed out at the press and likened the media to crabs scrambling to get out of a bucket and in the end pulling each other down.

More recently, in a televised nationwide address to defend his administration against charges of benefitting from the pork-barrel scandal, Aquino gave broad hints that he suspected parts of the media to be part of a conspiracy to shift the blame for the scandal on his government.

Media analysts say the President’s antagonistic tone against the media may in part have a role in the increasing numbers of media harassment and murders.

“There is a perception in the bureaucracy including the politicians, the local government units, and the military, that he does not like the media,” says Teodoro of Aquino. “Where does this come from? From his frequent criticisms of media.”

“In 2012, there were four instances in major media gatherings in which he was very critical of the media,” notes Teodoro, who is also CMFR’s deputy director. “That can have some effect on the kind of boldness that some local officials are acquiring in preventing journalists from covering, in barring journalists from attending functions, in filing libel suits and outright assaults on journalists. When the President speaks, he is the most powerful man in the Philippines.”

This antipathy to the media is also reflected in how Aquino has parried calls for the passage of the Freedom of Information Act. While the President’s communications secretaries have long indicated their support for the bill’s passage, Aquino has made known his discomfort with a media that has formidable clout.

“His antipathy toward FOI has implications in the minds of many people,” comments Teodoro. “One of the many reasons they have cited is because his sense is that media has become too powerful.”

“His words are not harmless,” says NUJP’s Paraan. “Whatever he says, that is the signal that his men get. If in your statement it is clear that he does not believe that media should be independent, what are you telling your men? In a way, this is also one of the reasons why the killings continue.”

“(The) killing of journalists effectively subverts the reason for having a democratic government,” says FFFJ legal counsel Prima Quinsayas. “I haven’t heard Noynoy (President Aquino) say ‘stop media murders’ in all of his SONAs (State of the Nation Addresses).”

Not in SONA anymore

PCIJ compiled President Aquino III’s four State of the Nation Addresses (SONAs) for this story. The SONAs show a downward trend in discussing, and even then vaguely, how his administration was going to address the continuing culture of impunity.

In his first SONA, Aquino mentioned the state of impunity in the country especially to media killings. The President, however, indirectly put the responsibility on media practitioners – ergo, the blame of the continuing killings as well. Addressing “our friends in media,” he said, “I trust that you will take up the cudgels to police your own ranks.”

Aquino added, “May you give new meaning to the principles of your vocation: to provide clarity to pressing issues; to be fair and truthful in your reporting, and to raise the level of public discourse.”

During his 2011 SONA, Aquino discussed extrajudicial killings, albeit briefly. He said, “We are aware that the attainment of true justice does not end in the filing of cases, but in the conviction of criminals. I have utmost confidence that the DOJ is fulfilling its crucial role in jailing offenders, especially in cases regarding tax evasion, drug trafficking, human trafficking, smuggling, graft and corruption, and extrajudicial killings.”

Curiously, in 2012, Aquino no longer made reference to the state of impunity, extrajudicial killings, or media killings. By 2013, he made no substantive mention on impunity, extrajudicial killings, or media killings, save for a brief aside on how the Bureau of Immigration (BI) let slip former Palawan Governor Joel Reyes and his brother, former Coron Mayor Mario Reyes – prime suspects of masterminding the killing of broadcaster Gerry ‘Doc’ Ortega – out of the country.

“If you think about it, you get a President that publicly scolds the national media,” Quinsayas says. “What kind of message is that sending out to those who do not like the way Philippine media works in terms of the watchdog role? But more importantly, I think it’s because if you listen at his previous State of the Nation address, there is actually no explicit agenda referring to press freedom.”

Paraan adds that whenever the President criticizes the media after a negative report on his administration, there is an impact on the public’s perception of the media and the bureaucracy. Says Paraan: “What you’re saying to the media is that they should not criticize you.”

For his part, Commission on Human Rights Commissioner Jose Manuel S. Mamauag says the rise in the number of media murders during the Aquino administration may be due to a deadly combination where journalists have the freedom to publish and broadcast yet lack the kind of protection that would guarantee their safety.

Such safety nets, Mamauag says, include the long-delayed FOI bill, which would reduce the risk on reporters since data-gathering itself would no longer be an antagonistic exercise.

Coloma meanwhile says the President was just asking media for “basic fairness” and more context in reportage. He repeats Aquino’s complaint that while foreign news agencies report on the country’s improving economic indicators, local media still focus on negative stories.

“It never crossed the President’s mind that, in calling the attention of the media, it would be an indirect attack on the media,” Coloma says. “We have no such mindset. We want the press to be free. It’s just the sense of fairness. He is just calling for a sense of fairness.”

Coloma says there may be a “divergence of views” in the manner by which the government and the media look at each other’s roles. Media’s watchdog role may no longer be appropriate for the post-martial law times, he says.

“There must be a leveling of concerns here,” he says. “What brings about that continuing mindset that the media will continue to play the role of watchdog? A watchdog is a dog. A dog guards a house against robbers. The dog will chase and hurt the robber. Is it correct to characterize the government as a robber that will invade the houses of citizens?”

Coloma also disputes charges by media groups that Aquino has made no clear statement against media murders. He asserts, “He views these matters with serious urgency and importance. If not he himself, it is the Secretary of Justice who has sufficiently articulated the government’s concern, and she is the alter ego of the President who reflects his thinking.”

A superbody is born

Fortunately, while the President appears to have made missteps on a personal level, his administration appears to have made some advances on a policy level.

In November last year, Aquino issued Administrative Order No. 35, creating the Inter-Agency Committee on Extra Legal Killings, Enforced Disappearances, Torture and Other Grave Violations of the Right to Life, Liberty, and Security of Persons. While that mouthful seems to be yet another layer of bureaucracy, or another superbody on top of a superbody, the new committee appears to have a clearer setup for coordination and organization – at least on paper.

The committee is headed by the Justice Secretary, and includes among its members representatives from the Philippine National Police, the military, the Interior Department, the National Bureau of Investigation, and even the Commission on Human Rights.

What makes this new superbody different is the new tack it takes on investigating crimes against journalists and activists. Before, prosecutors had to make do with whatever evidence the local police sees fit to give them. This time around, the prosecutors are to take part in the investigation and data gathering at the police level.

This is to ensure that whatever evidence gathered by police is gathered and handled in a way that is accepted by the courts. This also ensures the quality of evidence gathering and investigation, by introducing a legal framework to the investigation.

“Ordinarily, prosecutors do not go with the investigations,” says Justice Undersecretary Baraan. “They just leave it up to the NBI (National Bureau of Investigation) and the police who then file the case. That was the only time that they would come in.”

“The difference now,” he says, “is that the prosecutor is involved from the start. There is a legal background to determine if the evidence is admissible or not.”

He says the Justice Department had already designated 400 AO35 prosecutors who “will be tasked to go along with the law enforcers on the ground.”

“That is the paradigm shift that we are now adopting,” Baraan says.

Prosecutors’ burden

No doubt, the prosecutors’ involvement in the actual investigation and data gathering is laudable. But then the 400 “AO35 prosecutors” are not new prosecutors. In truth, they are old prosecutors who have just been given more work – this time in the field with the police. In other words, public prosecutors, many of whom are already saddled with too many cases, now have the additional task of going out with policemen to investigate such crimes.

In its aborted meeting with President Aquino in 2010, the FFFJ Board of Trustees had even hoped to raise the issue of overworked public prosecutors and the need to hire more prosecutors to ease the case load.

Before the AO35 prosecutors were tasked to do police investigation as well, public prosecutors were already dealing “unrealistically with 100 cases” each, says Quinsayas. She adds that her “fiscal friends tell me that that (100 cases per prosecutor workload) is a modest estimate.”

When PCIJ pointed out this little detail to a member of the technical working group of the Inter-Agency Committee, the official replied: “We will just have to work with what we have.” — With reporting and research by Ed Lingao, Cong Corrales, and Fernando Cabigao Jr., PCIJ, November 2013