Duterte’s budget priorities, and a look back at the Aquino years

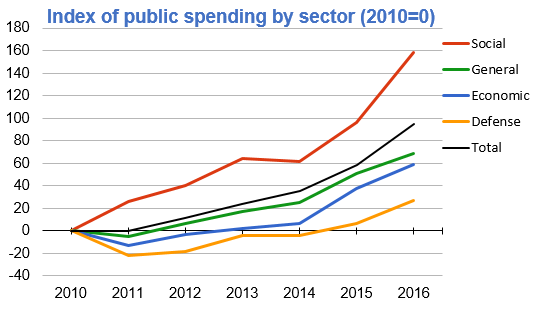

If I were to sum up the Aquino years in one chart, I would use this:

It depicts the growth of public spending in various sectors corresponding to Pres. Aquino’s time in office from 2010 to 2016, using 2010 as the benchmark. Above the zero baseline spending in an area is expanding compared to its 2010 level. Below it, spending is contracting.

We can see that in the first half of the Aquino years, significant growth only occurred in social services (education, health and social welfare). All other forms of spending declined in the first year. As a result, total disbursements excluding interest payments declined by 0.1% in 2011, falling by 1% point as a share of GDP from 17% down to 16%.

Aquino’s Fiscal Restraint

Pres. Aquino was hesitant to raise spending in public infrastructure projects (i.e. economic services), fearful that his predecessor Mrs. Arroyo had left behind questionable contracts and corrupted the bureaucracy. He spent the first three years of his presidency seeking to exorcise her ghost.

The chronic under investment that Mr Aquino’s circumspection bred led to a halving of the GDP growth rate in 2011. His budget chief tried to pump prime the economy through the Disbursement Acceleration Program in 2012 and 2013. This program was shot down by the courts after whistle blowers exposed rampant corruption within it.

Mr Aquino refused to support new revenue measures. This placed a limit on how much his government could spend. The passage of the sin tax reform laws following the mid-term elections of 2013 eased that constraint a bit. It gave the cabinet confidence to raise spending to keep up with revenues.

Playing a game of catch-up

Pres. Aquino made social spending a hallmark of his administration. His mother’s administration felt constrained to honor all debts entered into by the deposed dictator Ferdinand Marcos. This left little room for any other form of spending. By the time Mr. Aquino left office, spending on social services had increased to over a trillion pesos and occupied a third of total spending.

Public anger over years of neglect in mass transit, land transportation, airport management, power supply and internet and telecommunications regulation forced the government to respond by spending more on economic services. Instability in the South China Sea and continued unrest in Mindanao also provided new impetus to spend for national defense.

General services also received a big boost after Mar Roxas took over the Department of the Interior and Local Government. Sec. Roxas was seeking to succeed Pres. Aquino in 2016. He became deeply unpopular due to the slow government response following Super Typhoon Haiyan. Sec. Roxas sought to regain popularity by pouring money into the police department. He also administered the bottom up budgeting (BUB) program, a pot of money that his department awarded to local government units.

Duterte’s Opening Fiscal Gambit

Pres. Duterte’s first budget demonstrates almost a seamless continuity with the latter part of the Aquino years (see chart below). It maintains the upward trajectory in all major sectors left by Mr. Aquino without skipping a beat. There is no apparent disruption, unlike the first year of his predecessor.

You would not think this is the case, given the noise of his first six months in office. Pres. Duterte has made some very controversial moves in prosecuting his war on drugs, allowing the Marcos burial and dealing with the South China Sea issue. He has broken with the establishment’s approach in these areas. In handling budget priorities though, he has stayed the course.

His forward estimates for 2018 and 2019 signal a strategic shift. The economic team has announced tax reform measures that would lower corporate and income taxes, in exchange for other forms of revenues. The combined measures would give him the fiscal headroom to undertake expansive programs.

Duterte’s Budget Priorities

The Duterte administration intends to use this fiscal space to ramp up spending on capital outlay (see chart below). As a candidate, Pres. Duterte promised to raise infrastructure spending to 5% of GDP or above. Pres. Aquino hesitated to tinker with the tax system. Pres. Duterte has signaled his intention to do so to push development in the countryside from the get go.

This will result in a fiscal deficit of 3% of GDP (see chart below). His budget chief says this is sustainable. All of Pres. Aquino’s budgets programmed a 2-2.5% budget deficit. They seldom materialized because of chronic under spending. It is an unknown fact that in three of his six years in office, from 2013 to 2015 the consolidated public sector, which includes government corporations, produced surpluses.

Challenges Ahead

Several challenges lie ahead for the Duterte administration. Congress has been very slow to tackle the tax reform package that the Palace has submitted. The budget assumes these will kick in by 2018. Some have questioned this assumption. There could even be some erosion of revenue if Congress waters down some of the sin tax reform measures about to take effect.

Foreign investment pledges have declined, due in part to the many controversial statements the president has made against Western leaders. The global economy could experience greater instability with the assumption of Donald Trump to the US presidency. Bond markets are already pricing this in. The era of cheap money may be coming to an end. Pres. Aquino may have wasted a golden opportunity to raise spending under such benign conditions.

Could Pres. Duterte’s administration right that mistake? Ratings agencies see the Philippines as a bright spot in Asia. They expect the country to outshine all others in the region except India in terms of growth. The challenge for Mr. Duterte would be to make that growth felt by his people across all social classes and regions. He says he is not an economist and would rather leave it to his team to oversee fiscal and economic policy. He needs to support that team when it counts. Deferring to and supporting them may yet be the best thing Mr. Duterte ever does in his time in office.

(Source of all charts: author’s calculations using DBM Budget Papers found on www.dbm.gov.ph)

About The Author

Emmanuel Doy Santos

The author works as a development consultant and policy analyst in Adelaide, South Australia and Manila, Philippines. He is also the founder of the 2Klas Program, which equips inner city youth in Metro Manila with 21st Century skills. He has a Facebook page @CuspPH and tweets as @cusp_ph. He blogs and hosts a podcast on htttps://cusp-ph.blogspot.com.

Budget priorities: from Aquino to Duterte

Duterte’s budget priorities, and a look back at the Aquino years

If I were to sum up the Aquino years in one chart, I would use this:

It depicts the growth of public spending in various sectors corresponding to Pres. Aquino’s time in office from 2010 to 2016, using 2010 as the benchmark. Above the zero baseline spending in an area is expanding compared to its 2010 level. Below it, spending is contracting.

We can see that in the first half of the Aquino years, significant growth only occurred in social services (education, health and social welfare). All other forms of spending declined in the first year. As a result, total disbursements excluding interest payments declined by 0.1% in 2011, falling by 1% point as a share of GDP from 17% down to 16%.

Aquino’s Fiscal Restraint

Pres. Aquino was hesitant to raise spending in public infrastructure projects (i.e. economic services), fearful that his predecessor Mrs. Arroyo had left behind questionable contracts and corrupted the bureaucracy. He spent the first three years of his presidency seeking to exorcise her ghost.

The chronic under investment that Mr Aquino’s circumspection bred led to a halving of the GDP growth rate in 2011. His budget chief tried to pump prime the economy through the Disbursement Acceleration Program in 2012 and 2013. This program was shot down by the courts after whistle blowers exposed rampant corruption within it.

Mr Aquino refused to support new revenue measures. This placed a limit on how much his government could spend. The passage of the sin tax reform laws following the mid-term elections of 2013 eased that constraint a bit. It gave the cabinet confidence to raise spending to keep up with revenues.

Playing a game of catch-up

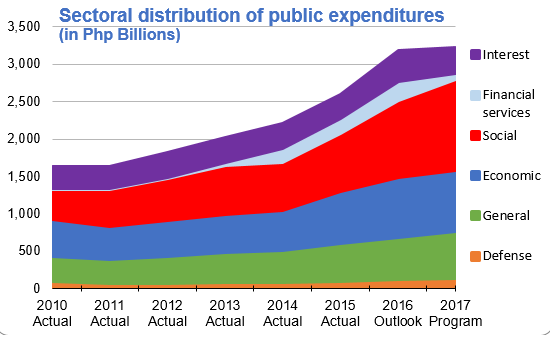

Pres. Aquino made social spending a hallmark of his administration. His mother’s administration felt constrained to honor all debts entered into by the deposed dictator Ferdinand Marcos. This left little room for any other form of spending. By the time Mr. Aquino left office, spending on social services had increased to over a trillion pesos and occupied a third of total spending.

Public anger over years of neglect in mass transit, land transportation, airport management, power supply and internet and telecommunications regulation forced the government to respond by spending more on economic services. Instability in the South China Sea and continued unrest in Mindanao also provided new impetus to spend for national defense.

General services also received a big boost after Mar Roxas took over the Department of the Interior and Local Government. Sec. Roxas was seeking to succeed Pres. Aquino in 2016. He became deeply unpopular due to the slow government response following Super Typhoon Haiyan. Sec. Roxas sought to regain popularity by pouring money into the police department. He also administered the bottom up budgeting (BUB) program, a pot of money that his department awarded to local government units.

Duterte’s Opening Fiscal Gambit

Pres. Duterte’s first budget demonstrates almost a seamless continuity with the latter part of the Aquino years (see chart below). It maintains the upward trajectory in all major sectors left by Mr. Aquino without skipping a beat. There is no apparent disruption, unlike the first year of his predecessor.

You would not think this is the case, given the noise of his first six months in office. Pres. Duterte has made some very controversial moves in prosecuting his war on drugs, allowing the Marcos burial and dealing with the South China Sea issue. He has broken with the establishment’s approach in these areas. In handling budget priorities though, he has stayed the course.

His forward estimates for 2018 and 2019 signal a strategic shift. The economic team has announced tax reform measures that would lower corporate and income taxes, in exchange for other forms of revenues. The combined measures would give him the fiscal headroom to undertake expansive programs.

Duterte’s Budget Priorities

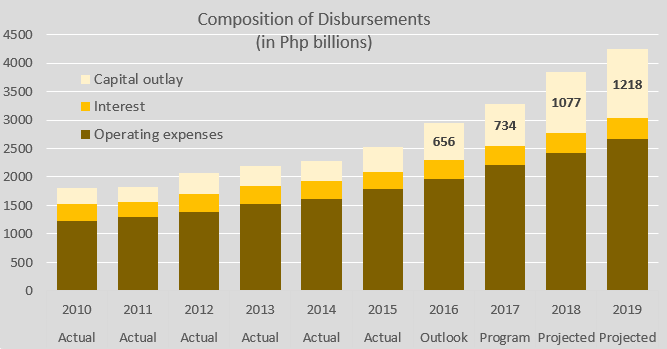

The Duterte administration intends to use this fiscal space to ramp up spending on capital outlay (see chart below). As a candidate, Pres. Duterte promised to raise infrastructure spending to 5% of GDP or above. Pres. Aquino hesitated to tinker with the tax system. Pres. Duterte has signaled his intention to do so to push development in the countryside from the get go.

This will result in a fiscal deficit of 3% of GDP (see chart below). His budget chief says this is sustainable. All of Pres. Aquino’s budgets programmed a 2-2.5% budget deficit. They seldom materialized because of chronic under spending. It is an unknown fact that in three of his six years in office, from 2013 to 2015 the consolidated public sector, which includes government corporations, produced surpluses.

Challenges Ahead

Several challenges lie ahead for the Duterte administration. Congress has been very slow to tackle the tax reform package that the Palace has submitted. The budget assumes these will kick in by 2018. Some have questioned this assumption. There could even be some erosion of revenue if Congress waters down some of the sin tax reform measures about to take effect.

Foreign investment pledges have declined, due in part to the many controversial statements the president has made against Western leaders. The global economy could experience greater instability with the assumption of Donald Trump to the US presidency. Bond markets are already pricing this in. The era of cheap money may be coming to an end. Pres. Aquino may have wasted a golden opportunity to raise spending under such benign conditions.

Could Pres. Duterte’s administration right that mistake? Ratings agencies see the Philippines as a bright spot in Asia. They expect the country to outshine all others in the region except India in terms of growth. The challenge for Mr. Duterte would be to make that growth felt by his people across all social classes and regions. He says he is not an economist and would rather leave it to his team to oversee fiscal and economic policy. He needs to support that team when it counts. Deferring to and supporting them may yet be the best thing Mr. Duterte ever does in his time in office.

(Source of all charts: author’s calculations using DBM Budget Papers found on www.dbm.gov.ph)

Related Posts

Dis-krimi-nasyon sa Trabaho

Japan’s Historical Idiocy and Moral Depravity

Why I am against the cyber libel provisions in RA 10175 #cybercrimelaw – Sen @TgGuingona

About The Author

Emmanuel Doy Santos

The author works as a development consultant and policy analyst in Adelaide, South Australia and Manila, Philippines. He is also the founder of the 2Klas Program, which equips inner city youth in Metro Manila with 21st Century skills. He has a Facebook page @CuspPH and tweets as @cusp_ph. He blogs and hosts a podcast on htttps://cusp-ph.blogspot.com.