FOI Under Quarantine

Confusing, scant, missing, denied info on programs, contracts, subsidy funds

By The Right to Know, Right Now! Coalition

FOR 15 weeks running, from March 29 to July12, 2020, the Right to Know, Right Now! Coalition (R2RKN) conducted a constant effort to access and monitor the release of public information and documents relevant to various initiatives that were supposed to be part of government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The effort drew the active participation of three part-time staff and 14 volunteers from 11 civil-society organizations. In all, they rendered some 2,600 work hours across a 105-day period.

R2RKN moved 27 letters via email and 11 non-email and phone inquiries, and 7 requests via government’s e-FOI portal. The letter exchange drew 54 email replies from the agencies, including six via the e-FOI portal and one referral to another agency.

To complement the public request effort, R2RKN also launched a parallel “FOI Tracker” dashboard that involved scouring, scraping, and monitoring the data, documents, and public statements lodged in 50 official websites; four data dashboards; and 59 social-media accounts (Twitter and Facebook) of national and regional government agencies.

The R2RKN’s team also watched and monitored 86 “Laging Handa” public briefings by the Presidential Communications Operations Office (PCOO), apart from 81 virtual pressers by the Department of Health (DOH), which similarly aired online and on television during the period.

Too, through the weary hours of midnight to dawn, R2RKN listened in to the 20 public addresses by President Rodrigo R. Duterte in the last 15 weeks.

After all, the “Bayanihan to Heal as One Act” or Republic Act No. 11469 that a special session of Congress enacted on March 23, 2020 gave President Duterte broad powers to authorize emergency or negotiated procurement of goods and services, as well as to “reallocate, realign, and reprogram” up to about PhP275 billion of the national budget approved for 2020 to address the COVID-19 pandemic across three-month period or until June 24, 2020.

From this 15-week monitoring project a few major observations have emerged:

- Coordination among the various government agencies – national, regional, local – seems wanting. Incremental numbers on COVID-19 cases are reported daily but scant information has been offered regularly on the use of COVID-19 budgets, subsidy fund recipients, and assistance programs for the most affected economic sectors.

- Programs to address the lingering public health crisis and its impact on citizens’ livelihood and the national economy over the medium- and long-term remain unclear and incoherent. Senior officials have discussed the issues largely via press briefings that highlight incremental achievements by the day, more than gaps in program implementation and further remedial interventions, and broad directions for the nation in the next six months to one year, or for a longer period of time.

- The President’s role in managing the crisis has been reduced to that of a talking head on late-night TV pressers, aired live or pre-taped weekly or fortnightly. In most of his 20 public addresses in the last 15 weeks, the President has largely read from reports of agencies or repeated statements of officials in charge of specific programs to respond to COVID-19.

Instead of explaining or clarifying policies or policy directions, most of these events showed the President going off-topic to his oft-repeated criticisms of independent media, the left, corruption in government, and “oligarchs” in the business community. He did not entertain questions from reporters in nearly all these events.

Still and all, R2RKN’s massive effort to monitor and access information during the pandemic drew not-so-good results in terms of the quality, completeness, and scope of information and data provided by 12 national government agencies that received access-to-information requests from R2RKN. These agencies are:

- The Office of the President and Office of the Executive Secretary;

- Inter-Agency Task Force for the Management of Emerging Infectious Diseases (IATF-EID);

- Department of Health (DOH);

- Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (PhilHealth);

- Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD);

- Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE);

- Overseas Workers Welfare Administration (OWWA);

- Department of Agriculture (DA);

- Department of Budget and Management (DBM);

- Philippine Government Electronic Procurement System (PhilGEPS);

- Balik Probinsya Program Council, through the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA), which referred the request to the National Housing Agency (NHA); and

- Department of Information and Communications Technology (DICT)

R2RKN had asked these agencies to disclose and release 35 sets of information, data, and documents, notably:

- Guidelines on the implementation of programs/projects, 12 requests;

- Budget and procurement-related data, 11 requests;

- Status of program implementation, six requests;

- Monitoring of medical cases, three requests; and

- Data on the disbursement of the Social Amelioration Program (SAP) funds, three requests.

By all indications, these agencies were invariably unprepared, unready, unequipped, or even willfully ungenerous with data on all these categories of information and data. Of the 35 requests filed by R2RKN, the agencies gave complete information and data on only four requests (three guidelines and one medical monitoring report).

Most exasperating of all, the agencies gave R2RKN only partial or incomplete information on 23 more requests, and no information at all on six other requests.

By what rules programs should run, whether these are running well or not, and how taxpayers’ monies are being spent – these are the data that these agencies had invariably did not, refused to, or would not release to R2RKN:

- Program guidelines (9 requests, including three with no information given);

- Status of program implementation (six requests, including two with no information given);

- Use and disbursement of public funds, “quick response funds,” subsidy grants, and budget for the Balik Probinsya Program (14 requests, including one with no information given).

Prior notice

To be sure, these agencies had received full and clear prior notice from R2RKN about this public request project. On March 29, 20020, R2RKN’s co-convenors wrote Health Secretary Francisco T. Duque III, chair of the IATF-EID, and Gen. Carlito G. Galvez, Jr. (ret.), implementer of the COVID-19 National Action Plan, informing them about the project’s launch.

In the letter, R2RKN said: “We are invoking our right to information to promote and safeguard transparency and accountability from public agencies, to access services and stake claims to other rights, and to facilitate positive initiatives like policy research, planning and on-the-ground action… and so that all Filipino citizens can be fully informed and empowered in the fight against the dreaded COVID-19.”

The public request for information, R2RKN said, builds on the values of transparency “for our citizens to feel reasonably confident that the government is taking care of them as best it should… assess how best and where we could help our public agencies and front-liners… report on where lapses exist and abuses happen, just as they can provide feedback and constructive inputs on initiatives that work… and know how best to protect themselves, their families, and their communities.”

“We need timely information so parallel initiatives in different communities and context can best respond to what and where the gaps are,” R2RKN added. “We need information so those we ask to volunteer for government and non-government initiatives understand full well what they are signing up for, feel how valued they are, and get the explanation on why despite this great value they may not be compensated justly.”

Public interest, according to R2RKN, “will be served best by transparency, accountability, and the steady flow of good, relevant, and useful information for all.”

Some stingy, some open

R2RKN’s project showed that a few agencies are more responsive and better organized, data-wise, than the great majority of those that received requests for information and data.

Truth be told, the agencies with the biggest amounts of budgets for emergency procurement, quick-response funds, and subsidy programs under the Bayanihan Act turned out to be the cellar-dwellers in terms of transparency and willingness to disclose the data requested by R2RKN.

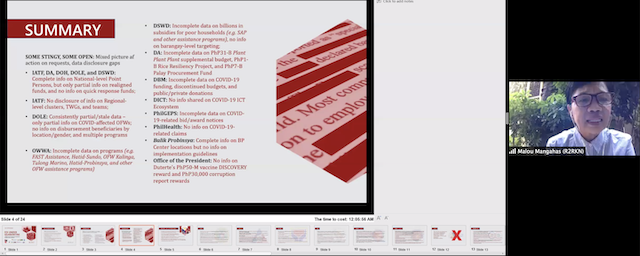

By agency action on these requests and the gaps in their data disclosures, a mixed picture emerges:

- The IATF, DA, DOH, DOLE, and DSWD shared complete data on the point persons or units, on the national level, that can receive inquiries from the public but only partial information could be obtained about agency funds that had been reprogrammed, reallocated, and realigned, or worse, no information at all on quick response fund allocations and recipients.

- IATF, however, did not disclose the composition and identities of those who are members of its regional clusters, technical working groups, and regional response teams.

- DOLE was absolutely consistent in sharing only partial and stale data on the status of implementation of multiple programs under its fold, and failed to give information on the number of beneficiaries and total amounts disbursed by city/municipality, by OFW destination country, and by gender under its fold. These include the COVID-19 Adjustment Measures Program or CAMP, Tulong Panghanapbuhay sa Ating Displaced/Disadvantaged Workers Program or TUPAD, #Barangay Ko, Bahay Ko program or #BKBK, and Financial Assistance for Displaced Land-Based and Sea-Based Workers or DOLE-AKAP for Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs).

- DOLE also gave only partial data on the status of the numbers of OFWs affected by COVID-19; those who had returned or plan to return home; quarantine facilities for OFWs; those who had been displaced or repatriated; those repatriated who had been sent to their home provinces or remain stranded; and those awaiting deployment overseas.

- OWWA, like DOLE, was distinctly incomplete as well with the data it shared on the following programs for OFWs; FAST (Food, Airport, Shelter, and Transportation) Assistance; Hatid-Sundo; OFW Kalinga; Tulong Marino; Hatid-Probinsiya; assistance to stranded OFWs in the regions; and related welfare programs.

- OWWA, moreover, gave no information at all on its lists of beneficiary-OFWs by program, by type of benefits/assistance received, by destination country, by origin province (city/municipality), and by gender.

- DSWD shared only incomplete data on the billions of pesos in subsidy programs for the millions of poor households. It gave only partial data on the requests of R2RKN for: allocations of the emergency subsidy of PhP5,000 to PhP8,000 a month for two months; guidelines and updates on the implementation of Assistance to Individuals in Crisis Situation (AICS) amid COVID-19; and specific enhancements made and allocations of the Expanded and Enhanced Pantawid Pamilya Pilipino Program.

- DSWD gave no information at all on the barangay-level data of the National Household Targeting System (NHTS).

- DA gave only partial data in response to several requests from R2RKN, including the breakdown and brief description per component of the PhP31-billion supplemental budget for the Plant Plant Plant program; components of the “Rice Resiliency Project”; allocation of the PhP1-billion loan facility for farmers, fishers, and agri-fishery MSEs; and guidelines on the fund allocation of National Food Authority’s PhP7-billion palay procurement fund.

- DBM shared only incomplete data on the following information sought by R2RKN: COVID-19 funding sources; discontinued budgets and COVID-19 attributed budgets under the 2019 and 2020 general appropriations acts; dividend remittances of government-owned and -controlled corporations (GOCC) dividends;

- DBM did not give complete data as well on the following items: COVID-19 Budget Data and Information of Fund Releases and Expenditures, including disaggregated data on the fund releases and expenditures presented by department/agency/special purpose fund; and breakdown of the amount of the reallocation or attribution, actual expenditure/disbursement.

- DBM gave only partial data on COVID-19 donations from public and private sources, with corresponding amount or value of in-kind and cash donations received and dispatched.

- DBM did not share complete data on COVID-19 Financing Requirement, including the projected sum of financing needed for COVID-19 response, information on the sources/ options of financing available, and detailed real-time or up-to-date reports on the national government’s cash position.

- DICT shared no information at all about its COVID-19 ICT Ecosystem.

- PhilGEPS gave only some copies of the bid and award notices related to COVID-19 response.

- PhilHealth has not released detailed information on claims and disbursements made related to COVID-19 cases. Asked for details of implementation of PhilHealth Advisory No. 2020-022, and Circular Nos. 2020-0009, 2020-0011, and 2020-0012, the agency could not give any information on the following: number of patients whose healthcare costs where fully covered by PhilHealth; total cost per hospital/health facility; number of cases and total claims approved per hospital/health facility; number of claims and total amount disbursed per patient and per benefit package under each circular; and number of recipients of full financial risk protection, and total amount disbursed.

- The Balik Probinsya Program Council was established by Executive Order No. 114, which created the “Balik Probinsya, Bagong Pag-asa Program.” R2RKN requested but did not receive information at all from the NEDA (a council member) about the implementing guidelines of this program.

- The Balik Probinsya Program Council managed to give the complete location of its Balik Probinsya Centers in the country but shared only partial data on the basis and menu/amounts of assistance to be provided to beneficiaries, and no data at all on its list of beneficiaries by type and amount of assistance given, and by destination province.

- The Office of the President was asked for information about President Duterte’s announcement that he would give PhP50 million as reward money to any Filipino who would develop a vaccine for COVID-19, and the PhP30,000 reward money to anybody who would report cases of corruption or irregularity in the use of the COVID-19 funds. Neither the OP nor the Office of the Executive Secretary gave any information at all about the President’s rewards programs.

Points of attention

Tardiness and disconnect seem to be strong suits of some officials in the Duterte administration. In a number of cases they made statements citing official issuances that had not been publicly disclosed, or had moved only in part on social-media accounts, without clear explanation or context. It would often take a week later or longer for the official issuances to emerge on the Official Gazette or official agency websites.

It took a while as well for IATF Resolutions to be uploaded publicly. R2RKN had to alert PCOO Assistant Secretary Kris Ablan about this, and finally on May 8 – nearly six weeks after the Bayanihan Act passed – the complete list of IATF Resolutions went up on the eFOI portal, COVID-19 PH portal, and the Official Gazette.

DOH:

By all accounts, the DOH is perhaps the only government agency that collects, processes, posts, and updates information on a regular basis – even more than once daily. However, the information that it has made available remain under challenge from persistent concerns, such as the daily case counts not giving a clear picture of how the virus is spreading; DOH has so far been missing its daily testing targets; the absence of a comprehensive picture of the capacity of local government units to respond to local cases.

Indeed, translating data to information, and information to policy and action, is a complicated process. Despite all the adjustments that DOH has made in its reporting, the data still do not show a clear picture of the pandemic situation in the country.

DOH also seems to be hung up on data per se for now. It has offered little explanation on where the new cases are emerging, and why; if and how they bunch up in certain locations (supermarkets, a particular barangay, areas) or sectors (HCWs, repatriates, highly-mobile workers). These are the types of information that can help Filipinos understand the situation and be on the alert on how to protect themselves better.

Merely showing data points (that keep going up, and in varying presentation formats) may only instill fear instead of vigilance.

Data adjustments indicate delays in validation that, in turn, indicate some inability of processing facilities to cope with increasing testing capacity. This prompts questions that include: Why and what is being done about it? If accrediting testing facilities takes time, are existing facilities not being refurbished and given additional resources so they can function better in the meantime?

DOLE:

DOLE’s move to publish curated information on regional official websites, Facebook accounts, contact numbers, and email addresses is commendable. This way, inquiries from the public are easier to address and be directed to relevant offices.

Still, while DOLE regularly releases announcements and updates status on the implementation of its programs, through news releases and statements, it might also explore other platforms like virtual pressers, daily infographics on the updates on the programs, chatBot, and others to educate and update the public.

Currently, the agency mainly uses its official website and social media accounts; most information on these platforms posted by DOLE, like the regional lists of CAMP beneficiaries, are not in uniform and open-data format.

Posting of official reports and issuances often lag behind DOLE’s announcements and statements, which can make them sound like mere rhetoric and lack accountability, especially if official reports and issuances to back these are nowhere to be found.

However, mere issuances are also not enough. Beyond cryptic information on its relief measures, it would be useful for DOLE to provide details about its plans and programs, and on their progress thereof. How things play out on the ground are instructive as to the adjustments that need to be done, the amount of work that needs to be addressed, and how successful DOLE’s interventions have been.

DSWD:

Overall, DSWD has been very generous with information in terms of policies and program implementation relating to the government’s COVID-19 response.

The DROMIC reports present crucial information with data breakdown down to provincial and key city levels. It fails, however, to present the number of families served by DSWD, LGUs, NGOs, and private partners.

Too, it does not disaggregate new from cumulative data, which would have been helpful in determining the current rate of response.

The attempt to publish the list of SAP beneficiaries was commendable. However, most of the links to regional data are often down and there is also no common format in the release of information from the regions.

DA:

Agriculture is critical in food security and providing livelihood, both of which have been weakened by the pandemic. Agricultural workers have been likened to medical front-liners helping Filipinos deal with this crisis. Agriculture holds prospects for the future in these areas and should be seen as playing a central role in the economy in the so-called ‘new normal.’

DA has thus gained an even more crucial role in the midst of the pandemic. But the department needs to improve the contents and tools in its platforms to achieve more transparency to allow the public to understand more fully the work that it does. While it deploys different platforms to publicize its programs, the amount of information it shares leaves much to be desired. Comprehensive reports regarding the ALPAS Program, for instance, are not available on its website.

DA has to address the paucity of information in its various platforms, and start releasing official documents to support and supplement their press conferences and press releases.

Some statements from the Department of Agriculture, moreover, need to be clarified:

- In press conferences and news releases, DA alternately uses ‘ALPAS Kontra sa COVID-19’ as ‘ALPAS Laban sa COVID-19’ to refer to a particular program, as well as takes to calling its Plant, Plant, Plant Program as Agri-4Ps in various instances. This inconsistency causes confusion as to the correct name of the programs.

- DA’s Rice Farmer Financial Assistance and Financial Subsidy for Rice Farmers are two separate unconditional cash transfer programs, with each involving PhP5,000 per eligible rice farmer-beneficiary. The difference between the two programs is not clearly communicated in virtual pressers and there are no official reports where the public can verify this information.

DBM:

DBM has been posting a summary of the COVID-19 budget releases initially through the President’s Report, then on its dedicated microsite. Data on donations are being released by the OCD online.

Since R2RKN filed its FOI request, DBM has updated its COVID-19 budget microsite four times, and has provided more categories/classifications on the budget releases.

Annexes on budget releases and donations have then been attached to the President’s Report.

The DBM Budget Division emailed an Excel file of the utilization of COVID-19 funds as of June 8, 2020. The file is not posted on the DBM website and is also missing in the President’s reports. DBM though is now preparing for a consolidated COVID-19 budget utilization report for funds used as of May 31, 2020.

While acknowledging the important role of the DBM in reporting COVID-19 budgets to the public, it could further push the boundaries of budget transparency.

Citizens deserve real-time or up-to-date budget databases that provide complete and consolidated trail of COVID-19 spending in all agencies involved in the response and recovery initiatives – from fund sources to disbursement, including updates on the national government cash position – in order to arrive at a fuller picture of the COVID-19 budget utilization performance. Some agencies reported their budget spending in the President’s Report, but some did not.

DBM has to build on these transparency efforts by employing full disclosure of the budget data submitted by key agencies pursuant to its guidelines on austerity measures (National Budget Circular 580) and submission of budget utilization reports (Circular Letter 2020-9). This should be made available to the public through its existing web platform, with an option to download file/s in open data format.

More than the summaries, a more disaggregated level of datasets will be helpful in the budget monitoring initiatives of some citizen groups and civil society organizations.

More disaggregated data sets will be most useful in gauging the effectiveness of targeting programs and getting citizens’ involvement in evaluating the impact of various programs. Reporting of COVID-19 allocation and spending should continue even after the validity of the Bayanihan Law and the subsequent budgetary measures addressing COVID-19.

Constituents are also interested to know where the funds under the Bayanihan Grant were allotted and disbursed in their localities. The President’s Report on the utilization of funds under the Bayanihan Grant is limited to the liquidation of expenses. Breakdown of expenses down to the barangay level that were charged against this fund could be presented by Local Government Units.

It is recommended as well that DBM, OCD, or IATF issue a policy requiring agencies receiving subsequent in-kind donations from foreign and domestic, and public and private sources to post their corresponding cash equivalent in order to hold into account all COVID-19 resources in the country in monetary terms.

DICT:

DICT has not released any information regarding the COVID-19-related government apps and has not acknowledged the email of the coalition.

PhilGEPS:

Since the start of the enhanced community quarantine, not much COVID-19-related procurement information has been posted by PhilGEPS. This is because PhilGEPS makes quarterly updates on its dataset.

COVID-related information is uploaded in its portal, but keywords would have to be used when searching its portal.

At present, there is no specific category or tag for COVID items. Agencies instead upload emergency negotiated procurement notices of award in the Government Procurement Policy Board (GPPB) portal.

The GPPB, through Resolution 06-2020 (April 6, 2020) and Circular 01-2020 (April 12, 2020), developed the guidelines for emergency procurement and established an online portal for all COVID-19-related procurement under RA 11649 or the Bayanihan Law. The online portal contains market listings, project requirements, procuring entities, and awarded contracts among others.

On April 28, PhilGEPS uploaded on its website its quarterly update of bid and award notices. This spreadsheet covering January to March 2020 includes items procured for COVID-19 response, but because there is no separate tag or specific note about these items, citizens will have to search through dataset for keywords such as “face mask,” “personal protective equipment,” “coronavirus,” or “COVID-19.”

After identifying these contracts, the related documents such as bid notice and notice of award may then be requested from PhilGEPS. PhilGEPS staff have confirmed that they will provide such documents as long as the reference IDs have been identified.

PHILHEALTH:

PhilHealth’s daily infographics have been most useful in providing the general public with important announcements. It has yet to release detailed information on COVID-19-related claims and disbursements, however.

BALIK PROBINSYA PROGRAM COUNCIL:

Executive Order No. 114, “Institutionalizing the Balik Probinsya, Bagong Pag-asa Program,” was signed May 6, 2020. The program aims to decongest Metro Manila and promote regional development. It created a Balik Probinsya, Bagong Pag-asa Council to develop and implement guidelines for the program.

In several interviews, government agencies announced the amounts of cash assistance a beneficiary would receive when he or she applies to be part of the program. A website was established, containing an application form.

The first batch of beneficiaries left for Leyte on May 20. Each was said to have been provided PhP5,000 as transportation allowance and PhP15,000 for livelihood. As of this report, however, the implementing guidelines of the program have not been released. Too, there is no clear information on the website on what the applicants should expect when they go back to their provinces and the basis for the cash assistance they will receive.

OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT:

In his Talk to the People statement, May 19, President Duterte assured Filipinos that the government is transparent in handling the billions of government funds allocated for COVID-19. He declared that “we will be able to account for it except those that were malversed by the officials down dito sa local governments na nawala, then they have to answer for it.”

In an earlier statement, the President announced that he would give a PhP30,000 reward money to any Filipino who reports local government officials stealing government aid.

On May 11, R2KRN requested a copy of the official issuance on the reward money from the Malacañang Records Office. On May 20, the Coalition received a response that the information requested was not on file. This puts into question how serious the pronouncement is. Absent official documentation, implementation of programs is subject to varying interpretation and lacks accountability.

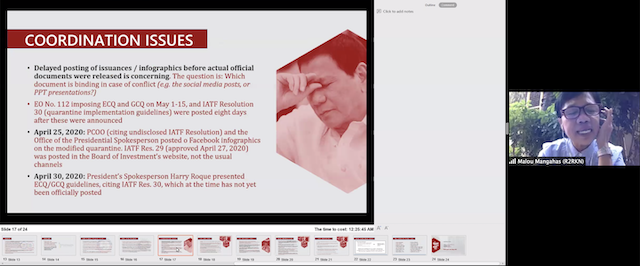

Coordination issues

The delayed posting of official issuances and posting of infographics and PPTs before the actual official documents were released pose coordination and implementation concerns. There is also the question of what document is binding if there is a case of conflict or misinterpretation — the social media infographics or the ppt presentation?

EO 112, on the imposition of Enhanced Community Quarantine (ECQ) and General Community Quarantine (GCQ) on May 1 to 15, and IATF Resolution No. 30, the Omnibus Guidelines on the Implementation of the Community Quarantine, were posted over a week later — eight days to be exact — after the same had been publicly announced, and a day after they were signed and approved.

In lieu of the official documents, infographics outlining the President’s pronouncements were released before the actual guidelines were finalized.

The PCOO on April 25 (citing an unnamed IATF Resolution), and the Office of the Presidential Spokesperson on April 28 (citing IATF Resolution No. 29), posted in their respective Facebook pages, infographics on the salient features of a modified quarantine. IATF Resolution No. 29, approved April 27, was posted in the Board of Investment website, and not in the usual channels.

In various press briefings and interviews, April 30, Secretary Harry Roque presented the guidelines on ECQ and GCQ, citing IATF Resolution No. 30, which at the time was not officially posted yet.

IATF Resolution No. 30 was publicly released and posted in The Official Gazette as part of EO No. 112 on May 1, 2020.

LGUs and OFWs

Unclear guidelines for programs tailored as a consequence of the pandemic have resulted in poor coordination among government units, putting at risk the people covered by such programs.

In a Facebook post addressed to DILG, OWWA, and NHA, Ormoc City Mayor Richard Gomez raised his concern over the lack of coordination with the LGUs in sending OFW repatriates from Metro Manila. He noted that he received a text message from OWWA about returning OFWs on the very same day that three planes will be arriving from Manila. According to the mayor, protocols on sending repatriates to provinces were not followed.

But a bigger concern than the controversy stirred by Mayor Gomez’s complaint is the impact such poor coordination has on the beneficiaries of the programs. Returning OFWs, for one, face the stigma of being potential virus carriers and may not feel welcome in their home provinces. Slow processing of the test results of some repatriates also exposes them to unnecessarily extended quarantine. That is, if they ever get to go home at all. As of this writing, thousands of OFWs remain billeted in different quarantine facilities in Metro Manila, and are still waiting for their COVID-19 test results, well beyond the 14-day mandatory quarantine period.

In the meantime, the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) has clarified that Balik Probinsya and Hatid Probinsya are two different government programs with different objectives.

Balik Probinsya is a long-term program for citizens who choose to relocate to the provinces, while Hatid Probinsya is an initiative to send home citizens stranded in Metro Manila due to travel restrictions imposed under ECQ. But official guidelines for both of these programs have yet to be issued.

On May 25, Presidential Spokesperson Harry Roque said that President Duterte had ordered government agencies to send home the 24,000 repatriated OFWs within a week. The President also ordered LGUs to accept the returning OFWs, and insisted that only the national government is allowed to impose travel restrictions due to national emergency. This was in response to reports that some LGUs had been refusing to accept returning OFWs for fear that they could be carriers of COVID-19.

DOH has released protocols on testing and quarantine but given that the volume of tests has exceeded the capacity to encode and analyze them, the public, especially the OFWs, and the local governments, are left confused on what to do next.

Where is DU30 in picture?

The President’s weekly submissions can become a mechanical read of agency accomplishments. So far, they have failed to report the challenges and limitations that agencies encounter in the implementation of their respective COVID-19 programs. Identifying the constraints is important to make sense of the delays and backlogs in distribution and reporting in order to address them.

The President addresses the nation on air, via online or television, with many of these addresses pre-recorded. The often late hours (with one address aired at 1:00 a.m) of airing affects how he communicates to the people, and indicates a lack of concern for people’s time. While these addresses are eventually uploaded in media and government social media sites, some members of the public still stay up late to catch him live or the original airing.

Of even bigger concern is that many of the President’s talks hardly cover important information the public needs to know, such as specific updates on the effectivity of quarantine orders.

The lack of details in the President’s public appearances has resulted in the need for his Spokesperson to later clarify or explain what the country’s chief executive said or did not say.

In a time of crisis, it is important for the head of state to be a source of reassurance. This is best done by clear and direct messaging, not one that is done by relay or reinterpretation.

More observations

- The IATF and the NAP are fully functioning, but the complete organizational structure, specific agency responsibilities, point persons, and contact information are not available in a consolidated form — all critical information that signal the plan and command, as well as direct people to relevant authorities.

- Beneficiary data released need to be evaluated and validated. Evaluation is an important basis for further clarifying apparent inconsistencies in reporting.

- Most data/information are not being released in open-data machine-readable format, which makes it harder for observers/researchers to export, cross-check, and make calculations.

- Crucial details are still not being released, including those regarding the breakdown of budget releases, information on PhilHealth claims and disbursements, and implementation guidelines of the BP2 Program.

- Assertions made public often need verification. One example was the government’s claim that “80% of Filipinos were satisfied with the government’s response to COVID-19,” based on a survey conducted by Gallup International Association (GIA) in partnership with the Philippine Survey and Research Center. There are issues around the use of the Gallup brand, putting the survey results in question.

Information is vital and should be a constant in public service. Readability and form are important, but timeliness and verifiability are equally, and to many, much more, essential.

While government agencies have been relatively proactive in releasing some COVID-19-related information via various modes and platforms, the level of openness, agency by agency, has been largely uneven.

R2RKN had asked and hoped that government would identify a central repository of information from its many agencies, and that this could offer correct, complete, and current information, and updated regularly.

It would be good to have Word file versions of all official guidelines and issuances to allow readers to mark, copy, and extract relevant provisions. Numbers should be in machine-readable format, not in text, pdf, or photo.

Most importantly, the basic guidelines and issuances should be released first (or at least at the same time as) before social-media cards or infographics, to avoid any confusion or misinterpretation.

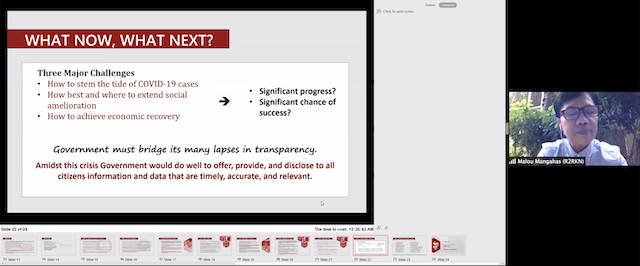

What Now, What Next?

For nearly four months now, slight to severe restrictions on mobility and other rights have been imposed on Filipino citizens. This has been generally accepted as necessary, or unavoidable, to deal with the continuing public health crisis that is COVID-19.

R2KRN’s public FOI request tracking initiative — formally requesting the information and datasets and proactively monitoring and scraping various platforms to check if these have been made public, instead of waiting for agencies to prepare these documents/records to exclusively respond to the coalition— recognizes the uniqueness of the situation and the difficulty of agencies to respond to information requests.

But it is also amidst this crisis that Government would do well to offer, provide, and disclose to all citizens information and data that are timely, accurate, and relevant.

The IATF is a whole-of-government mechanism to address the COVID-19 crisis. In an inter-agency setup, information is critical for shared understanding, effective planning and coordinated action. But the not-so-good results in terms of the quality, completeness, and scope of information and data that government has provided in the last 15 weeks raise alarm bells, and do not inspire confidence that the nation has moved to a better place.

Three major challenges confront the government: how to stem the tide of COVID-19 cases, how best and where to extend social amelioration, and how to achieve economic recovery. The paucity of information offers weak proof that there has been significant progress achieved in all these concerns thus far, or even significant chance of success to be achieved in time.

But first, government must bridge its many lapses in transparency. Reporting on what it had done does not suffice anymore, especially if its reports are incomplete or incoherent.

More than post-facto reports, government must inform and prepare all citizens about what it plans to do next, how interventions could be improved, and how the nation could move and heal as one in addressing the challenges of COVID-19, social amelioration, and economic recovery.