Part of an #Election2016 series called “What’s at stake?”

The post-PNoy president will inherit an economy that is growing faster than the previous 40 years. Because of this and the fiscal reforms initiated by the previous administration, the budget is coming into its own as the Philippines achieves middle income status. The government now has the “space” to deal with the country’s development challenges. Policy matters in a way that it didn’t before.

The contest for the presidency is now about who gets control of the budget, Spending previously was constrained by debt payments, so the battle was over who got control over off-budget items, such as the awarding of permits to exploit natural resources, granting of licenses and monopolies, “sale” of business regulation to vested interests, protection money from illegal activities, and granting of favorable loans and deals to business cronies.

Not that those things don’t happen anymore; they still do. It is just that now with the economy and fiscal space expanding, the budget, and policy matter in a way they haven’t before. And it is about time, because some of the long-term trends and global forces that the next president will face are quite daunting. Here they are, in no particular order.

PREMATURE DE-INDUSTRIALIZATION

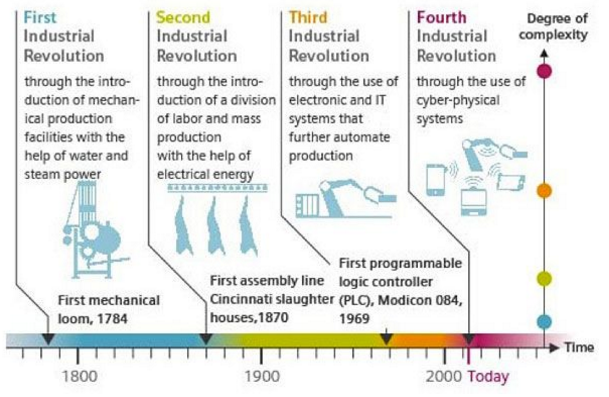

De-industrialization, or the decline of industrial capacity in a country, particularly in heavy industry or the manufacturing sector, is nothing new to the developing world. During the first industrial revolution from 1750 to 1870 India experienced deindustrialization, as the adoption of the steam powered loom made weavers in England more cost competitive. As a result, India’s share of global garments production fell from 25% in 1750 to 2% by 1900.

The second industrialization from 1870 to 1969, marked by the introduction of the assembly line, led to further divergence as incomes in the West rose leaving the rest of the world behind. The third industrial revolution from 1970 to 2000 produced deindustrialization in the West as globalization shifted labor intensive manufacturing to lesser developed countries, allowing their incomes to “catch-up” or converge again with the West.

Since 2001, we have been living through the fourth industrial revolution, in which robotics and complex algorithms are increasingly replacing humans in production. It has also led to the “gig” economy with apps like Uber converting the workforce into independent contractors rather than employees. As a result, deindustrialization in the developing world is occurring even before incomes have caught up with the West.

Image source: http://www.well-comm.es/

The process has already begun in the Philippines. Back in 2002, the industry sector contributed 34.6% to the total economic output of the nation. By 2014, it had declined to 31.4%. In 2001, manufacturing employed 10% of our workforce. By 2014, it had gone down to 8.3%. This is significant for several reasons. Firstly, as Norio Usui of the Asian Development Bank points out

The manufacturing sector has the highest intersectoral links in the economy. This implies that manufacturing is the leading sector that can stimulate growth in other sectors. If manufacturing could have a higher share, an expansion of the sector would create higher growth through its strong link effects with other sectors.

Secondly, as Usui also shows labor productivity in the business process outsourcing (BPO) industry was about $5,000 per worker in 2009, higher than other service sectors and that of the economy as a whole, which is a good thing. But it was still well below the level set by industry ($7,500) and manufacturing ($8,200).

Thirdly, since the BPO industry requirements for hiring at entry level positions include a college degree, it is unlikely to provide employment for low skilled workers. Only industry has historically offered these type of workers higher wages than what they would otherwise earn in the agricultural or low service sectors.

With the window for industrialization closing, the only option is to move up the value chain by producing more complex products. The good news is that the Philippines has the capacity to do this given the type of products it currently produces (see Hausmann and Rodrigo’s economic complexity rankings here). The bad news is that as it moves up the value chain, the demand for skilled workers will increase, and the demand for low skilled workers will decline, which will be a problem given the next developmental challenge.

LATE DEMOGRAPHIC TRANSITION

A high fertility rate has led to a growing population with a low median age. By the end of 2016, the population of the Philippines will be 102.25 million according to United Nations estimates. The median age will be 24.4 years, meaning half the population will be equal to or less than this age. The fertility rate will be 3.01 live births per woman, which translates to a population growth rate of 1.5% or an increase of 1.55 million residents per year.

By 2050, the population is projected to reach 148.26 million. The median age would have risen to 32 years. The fertility rate would have fallen to 2.2 live births per woman. Population growth would have slowed to 0.74%, but that still means an increase of 1.07 million per year. Older aged residents would account for 20% of the population, comparatively lower than our neighbors in the region. This late demographic transition to a low fertility, slow growing population will present a few challenges for the next president.

The highly celebrated “demographic dividend” or “sweet spot” which refers to a country having a greater proportion of its population entering the workforce and contributing to higher income, consumption and savings is not a certainty. As the Asian Development Bank noted in a 2011 report

The demographic dividend is not, however, an automatic consequence of favorable demographic changes. Rather, it depends on the ability of an economy to productively use its additional workers.

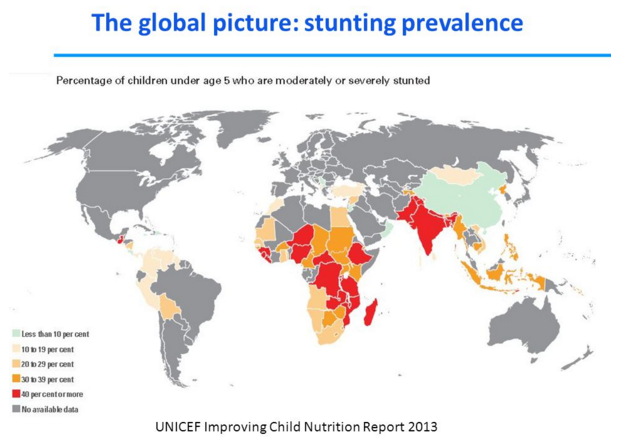

Productive use of new entrants into the workforce involves, firstly keeping the young population healthy, fit and well educated, so that it can engage in productive employment. This will be a big challenge given the problems of hunger, malnutrition and stunting that are still prevalent in the country (see chart). Stunting which takes place within the first two years of a child’s life irreversibly prevents neural networks of the brain from connecting. This limits a person’s capacity to complete any level of education.

As Dr. Jim Young Kim, head of the World Bank points out, this will be a problem as agriculture, which currently employs 31% of the Philippine workforce, increasingly becomes mechanized. The farm sector, which historically has been able to absorb workers with very low educational attainment, will start to displace workers. In the Philippines, the number of agricultural workers has fallen 3.7% from 12.2 million in 2011 to 11.8 million in 2014, despite a 5.6% rise in agricultural output from P679.8 billion to P717.8 billion during this period.

Without the mental capacity to perform complex tasks, the only place for displaced unskilled agricultural workers would be in the informal services sector of the economy. Casual agricultural workers will eventually wind up migrating to urban centers. The size of our urban population is set to rise from 45.8 million, or 44.8% of our total population in 2016, to 88.4 million or 59.6% by 2050. This will put a strain on our cities with informal settlers occupying land next to sensitive estuaries and rivers that become vulnerable to flooding.

Secondly, assuming we are able to feed, keep healthy and educate our young workforce, the next task would be to provide employment opportunities for all. With the advent of the fourth industrialization, in which robotics and complex algorithms are eliminating the need for low skilled workers in the industry and service sectors, this will be even more difficult in the coming years. The ADB suggests that

Younger Asian countries must strive to create enough job opportunities for their young workforce through active labor-market policies and vocational training programs. These countries can learn valuable lessons from the East and Southeast Asian countries that reaped big dividends in the past.

The middle income trap, a situation in which a country’s growth slows after reaching a certain level of development, is what the Philippines will fall prey to if it is unable to reap its demographic dividend. Social disparities in income and opportunity will become a barrier to growth and development, which will then lead to further social problems, unless properly addressed.

SEVERITY OF CLIMATE CHANGE

Climate change is a change in global or regional weather patterns associated with the increasing concentration of carbon dioxide and equivalent greenhouse gases in the atmosphere accumulated due to the exploration and burning of fossil fuels such as coal, oil and natural gas since the first industrial revolution of 1750. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in its 2014 report stated that

Climate change will amplify existing risks and create new risks for natural and human systems. Risks are unevenly distributed and are generally greater for disadvantaged people and communities in countries at all levels of development.

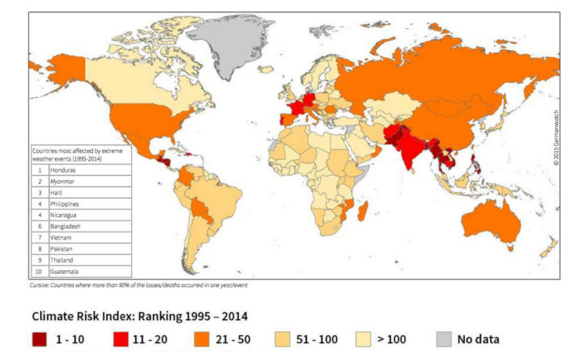

In the twenty years through to 2014, the Philippines was the fourth most affected country by climate change, according to the Global Climate Risk Index with 18,540 associated fatalities (averaging 927 per year) and $54 billion worth of damages to its economy (averaging $2.7 billion per year) during this time. In 2013 alone, Typhoon Haiyan struck and inflicted US$13 billion worth of damages and took 6,000 casualties.

Source: Germanwatch

In 2011, the Center for Global Development working paper predicted that on average about 5% of the Philippine population would be vulnerable to climate change by 2015. That is about 5 million that are at risk because they either live in vulnerable areas or may suffer lost income due to extreme climatic, weather disturbances. This includes drought brought on by the El Nino weather pattern, which is becoming more frequent and severe due to climate change, and the dwindling of fish stocks as the acidification of oceans increases.

Climate change will pose many risks and present many challenges to the next president including how to make the population and economy more prepared and resilient to severe weather occurrences, as well how to transition into a low carbon economy. At the Paris conference on climate change, the Philippine government committed to a reduction in emissions of 70%, relative to a business-as-usual scenario, on the condition of international support.

Aside from the challenges, there will also be opportunities to set-up sustainable industries, like renewable energy, energy efficient construction, electric-powered vehicles and transport, and resource efficient production. The Philippines can position itself to be at the forefront of such technology by incentivizing innovation and investment in such fields. It will be up to the next president to come up with a framework for doing so.

RE-EMERGENCE OF CHINA’S GEOPOLITICAL CLOUT

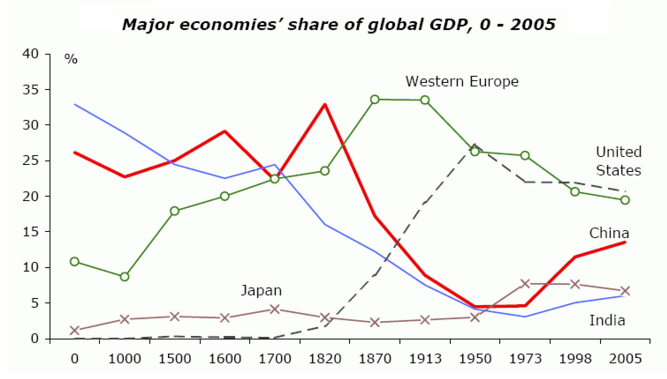

The re-emergence of China as a superpower in the 21st century will create many opportunities and challenges for the next president. I say re-emergence because up until 1830, China along with India, had been the dominant economies of the world accounting for about 50% of global GDP (see chart). China is currently the world’s second largest economy. A 2015 report by the Economic Intelligence Unit forecasts that it will surpass the United States to become the leading economy by 2026.

Image credit: http://fatknowledge.blogspot.com.au/

As it re-emerges as the leading global economy, China will increasingly assert itself on the world stage. It has started to do so in its own backyard, the South China Sea. Robert Kaplan likens China’s moves to that of the US when it was emerging as a superpower, when he wrote

China’s position here is in many ways akin to America’s position vis-à-vis the similar-sized Caribbean in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The United States recognized the presence and claims of European powers in the Caribbean, but sought to dominate the region nevertheless…Domination of the greater Caribbean Basin, moreover, gave the United States effective control of the Western Hemisphere.. And today China finds itself in a similar situation in the South China Sea.

Merriden Varral of the Lowy Institute says that aside from the importance of the South China Sea to international trade routes and as a potential source of energy, China’s motivations for asserting itself in the region come from a deeply held view regarding what it sees as “its rightful and respected place in the world… after the painfully remembered ‘Century of Humiliation’ beginning with the Opium Wars in the mid-1800s.” She goes on to say

China’s attitude towards the other claimants in the South China Sea also reflects a narrative of filial piety and familial obligation. In this view, China’s role in the region is that of a regional father figure and benevolent overseer of a peaceful region, in which its neighbours (should) willingly pay due respect. And, if China’s neighbours do not show the proper deference, this is seen to justify taking stronger measures to ensure that this familial order is respected.

China observes relationship-based governance, that is predicated on norms of reciprocity rather than a system of rules. Varral contends that if the International Court in the Hague decides in the Philippines’ favor to invalidate China’s territorial claims, China is more likely to react negatively and declare an air defense identification zone (ADIZ) in the South China Sea just as it did in the East China Sea.

An ADIZ is described by David Welch as “a publicly defined area extending beyond national territory in which unidentified aircraft are liable to be interrogated and, if necessary, intercepted for identification before they cross into sovereign airspace.” China’s installation of a powerful radar station and surface to air missiles on different islands in the South China Sea have boosted its capacity to monitor ships and planes passing through the Straits of Malacca, a critical shipping route between Malaysia and Indonesia, according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

The US and its allies in the region have been ramping up rhetoric, in anticipation of this decision, but this tactic runs the risk of reinforcing China’s view of the world ganging up on it, once again. The next president will have to engage with China diplomatically along with other players in the region to ensure that peace and stability is maintained, to enable our economies to prosper and continue to take advantage of the Asian Century.

SPREAD OF ISLAMIST IDEOLOGY

The spread of Islamist ideology is the last challenge the next president has to deal with. In March this year, the chairman of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, Al Haj Ebrahim Murad declared that ISIS would gain a foothold in the Philippines, if the next president failed to rescue the stalled peace process. This came after IS attacks in Jakarta had many security experts fear that the southern Philippines would be next. The leaders of Abu Sayyaf, which has links to Jemaah Islamiyah, a Salafi jihadist group, inspired by the same ideology as al-Qa’ida, have previously pledged allegiance to Islamic state.

The Islamic state, like al-Qaeda belongs to the jihadi school of thought, which seeks to reorder government and society in accordance with Islamic law, or Sharia. Late-20th century jihadism was influenced by the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt which promoted the restoration of the caliphate as the ideal system for the Islamic world, and Salafism from Saudi Arabia, a theological movement from within Sunni Islam, which seeks to purify the Islamic faith from idolators (shirk) that detract from the oneness of God (tawhid). According to the Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought,

A caliphate is an area containing an Islamic steward known as a caliph—a person considered a religious successor to the Islamic prophet, Muhammad (Muhammad ibn Abdullah), and a leader of the entire Muslim community.

The Sunni branch of Islam believes that as a head of state, a caliph should be elected by Muslims or their representatives, while followers of Shia Islam, believe a caliph should be an Imam chosen by God from the Ahl al-Bayt (the “Family of the House”, Muhammad’s direct descendants).

Salafis consider themselves to be the only true Muslims. They are opposed to what they see as the excessive veneration practiced by Shi’a muslims of the Prophet Muhammad’s family. Many salafis are also opposed to democrats, for assigning “partners” to God in legislation, which they see as the sole prerogative of the Divine legislator. As Cole Bunzel wrote

If jihadism were to be placed on a political spectrum, al-Qaeda would be its left and the Islamic State its right. In principle, both groups adhere to Salafi theology and exemplify the increasingly Salafi character of the jihadi movement. But the Islamic State does so with greater severity. In contrast with al-Qaeda, it is absolutely uncompromising on doctrinal matters, prioritizing the promotion of an unforgiving strain of Salafi thought.

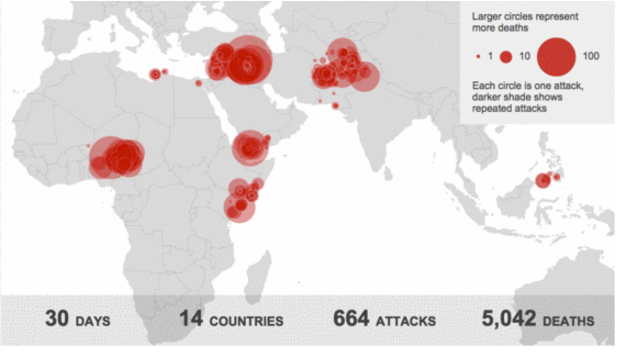

The Islamic State of Iraq began in 2006 and gained international recognition when it announced its plans of expanding into Syria in 2013. It rebranded itself as the Islamic State of Iraq and Sham, and after occupying most Sunni areas in the area in June 2014 declared itself a caliphate, or global Islamic empire. In November 2014 alone, the BBC recorded over 5,000 deaths worldwide as a result of Islamic State militant operations. Of that total 9 attacks resulting in 50 deaths took place in the Philippines (see chart).

ISIS attacks recorded in November, 2014

Source: BBC

The Bangsamoro Basic Law, which embodied the peace agreement brokered by Malaysia between the Philippine government and the MILF failed to clear congress after an encounter resulted in the death of 44 government special action forces in January 2015. The law would have increased the geographic area and powers of the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao and would have given this region a greater share of internal revenue and mining royalties. Congressional leaders feared that the would have given away too much power and autonomy, and created a state within a state.

It will be up to the next president to come up with a lasting peace agreement that would be amenable to the various stakeholders in the south. Failure to do so could pave the way for a greater influence of Islamic State operatives in the country, which would have significant repercussions for the growth and stability of the region.

5 Challenges for the Next President

Part of an #Election2016 series called “What’s at stake?”

The post-PNoy president will inherit an economy that is growing faster than the previous 40 years. Because of this and the fiscal reforms initiated by the previous administration, the budget is coming into its own as the Philippines achieves middle income status. The government now has the “space” to deal with the country’s development challenges. Policy matters in a way that it didn’t before.

The contest for the presidency is now about who gets control of the budget, Spending previously was constrained by debt payments, so the battle was over who got control over off-budget items, such as the awarding of permits to exploit natural resources, granting of licenses and monopolies, “sale” of business regulation to vested interests, protection money from illegal activities, and granting of favorable loans and deals to business cronies.

Not that those things don’t happen anymore; they still do. It is just that now with the economy and fiscal space expanding, the budget, and policy matter in a way they haven’t before. And it is about time, because some of the long-term trends and global forces that the next president will face are quite daunting. Here they are, in no particular order.

PREMATURE DE-INDUSTRIALIZATION

De-industrialization, or the decline of industrial capacity in a country, particularly in heavy industry or the manufacturing sector, is nothing new to the developing world. During the first industrial revolution from 1750 to 1870 India experienced deindustrialization, as the adoption of the steam powered loom made weavers in England more cost competitive. As a result, India’s share of global garments production fell from 25% in 1750 to 2% by 1900.

The second industrialization from 1870 to 1969, marked by the introduction of the assembly line, led to further divergence as incomes in the West rose leaving the rest of the world behind. The third industrial revolution from 1970 to 2000 produced deindustrialization in the West as globalization shifted labor intensive manufacturing to lesser developed countries, allowing their incomes to “catch-up” or converge again with the West.

Since 2001, we have been living through the fourth industrial revolution, in which robotics and complex algorithms are increasingly replacing humans in production. It has also led to the “gig” economy with apps like Uber converting the workforce into independent contractors rather than employees. As a result, deindustrialization in the developing world is occurring even before incomes have caught up with the West.

Image source: http://www.well-comm.es/

The process has already begun in the Philippines. Back in 2002, the industry sector contributed 34.6% to the total economic output of the nation. By 2014, it had declined to 31.4%. In 2001, manufacturing employed 10% of our workforce. By 2014, it had gone down to 8.3%. This is significant for several reasons. Firstly, as Norio Usui of the Asian Development Bank points out

Secondly, as Usui also shows labor productivity in the business process outsourcing (BPO) industry was about $5,000 per worker in 2009, higher than other service sectors and that of the economy as a whole, which is a good thing. But it was still well below the level set by industry ($7,500) and manufacturing ($8,200).

Thirdly, since the BPO industry requirements for hiring at entry level positions include a college degree, it is unlikely to provide employment for low skilled workers. Only industry has historically offered these type of workers higher wages than what they would otherwise earn in the agricultural or low service sectors.

With the window for industrialization closing, the only option is to move up the value chain by producing more complex products. The good news is that the Philippines has the capacity to do this given the type of products it currently produces (see Hausmann and Rodrigo’s economic complexity rankings here). The bad news is that as it moves up the value chain, the demand for skilled workers will increase, and the demand for low skilled workers will decline, which will be a problem given the next developmental challenge.

LATE DEMOGRAPHIC TRANSITION

A high fertility rate has led to a growing population with a low median age. By the end of 2016, the population of the Philippines will be 102.25 million according to United Nations estimates. The median age will be 24.4 years, meaning half the population will be equal to or less than this age. The fertility rate will be 3.01 live births per woman, which translates to a population growth rate of 1.5% or an increase of 1.55 million residents per year.

By 2050, the population is projected to reach 148.26 million. The median age would have risen to 32 years. The fertility rate would have fallen to 2.2 live births per woman. Population growth would have slowed to 0.74%, but that still means an increase of 1.07 million per year. Older aged residents would account for 20% of the population, comparatively lower than our neighbors in the region. This late demographic transition to a low fertility, slow growing population will present a few challenges for the next president.

The highly celebrated “demographic dividend” or “sweet spot” which refers to a country having a greater proportion of its population entering the workforce and contributing to higher income, consumption and savings is not a certainty. As the Asian Development Bank noted in a 2011 report

Productive use of new entrants into the workforce involves, firstly keeping the young population healthy, fit and well educated, so that it can engage in productive employment. This will be a big challenge given the problems of hunger, malnutrition and stunting that are still prevalent in the country (see chart). Stunting which takes place within the first two years of a child’s life irreversibly prevents neural networks of the brain from connecting. This limits a person’s capacity to complete any level of education.

As Dr. Jim Young Kim, head of the World Bank points out, this will be a problem as agriculture, which currently employs 31% of the Philippine workforce, increasingly becomes mechanized. The farm sector, which historically has been able to absorb workers with very low educational attainment, will start to displace workers. In the Philippines, the number of agricultural workers has fallen 3.7% from 12.2 million in 2011 to 11.8 million in 2014, despite a 5.6% rise in agricultural output from P679.8 billion to P717.8 billion during this period.

Without the mental capacity to perform complex tasks, the only place for displaced unskilled agricultural workers would be in the informal services sector of the economy. Casual agricultural workers will eventually wind up migrating to urban centers. The size of our urban population is set to rise from 45.8 million, or 44.8% of our total population in 2016, to 88.4 million or 59.6% by 2050. This will put a strain on our cities with informal settlers occupying land next to sensitive estuaries and rivers that become vulnerable to flooding.

Secondly, assuming we are able to feed, keep healthy and educate our young workforce, the next task would be to provide employment opportunities for all. With the advent of the fourth industrialization, in which robotics and complex algorithms are eliminating the need for low skilled workers in the industry and service sectors, this will be even more difficult in the coming years. The ADB suggests that

The middle income trap, a situation in which a country’s growth slows after reaching a certain level of development, is what the Philippines will fall prey to if it is unable to reap its demographic dividend. Social disparities in income and opportunity will become a barrier to growth and development, which will then lead to further social problems, unless properly addressed.

SEVERITY OF CLIMATE CHANGE

Climate change is a change in global or regional weather patterns associated with the increasing concentration of carbon dioxide and equivalent greenhouse gases in the atmosphere accumulated due to the exploration and burning of fossil fuels such as coal, oil and natural gas since the first industrial revolution of 1750. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in its 2014 report stated that

In the twenty years through to 2014, the Philippines was the fourth most affected country by climate change, according to the Global Climate Risk Index with 18,540 associated fatalities (averaging 927 per year) and $54 billion worth of damages to its economy (averaging $2.7 billion per year) during this time. In 2013 alone, Typhoon Haiyan struck and inflicted US$13 billion worth of damages and took 6,000 casualties.

Source: Germanwatch

In 2011, the Center for Global Development working paper predicted that on average about 5% of the Philippine population would be vulnerable to climate change by 2015. That is about 5 million that are at risk because they either live in vulnerable areas or may suffer lost income due to extreme climatic, weather disturbances. This includes drought brought on by the El Nino weather pattern, which is becoming more frequent and severe due to climate change, and the dwindling of fish stocks as the acidification of oceans increases.

Climate change will pose many risks and present many challenges to the next president including how to make the population and economy more prepared and resilient to severe weather occurrences, as well how to transition into a low carbon economy. At the Paris conference on climate change, the Philippine government committed to a reduction in emissions of 70%, relative to a business-as-usual scenario, on the condition of international support.

Aside from the challenges, there will also be opportunities to set-up sustainable industries, like renewable energy, energy efficient construction, electric-powered vehicles and transport, and resource efficient production. The Philippines can position itself to be at the forefront of such technology by incentivizing innovation and investment in such fields. It will be up to the next president to come up with a framework for doing so.

RE-EMERGENCE OF CHINA’S GEOPOLITICAL CLOUT

The re-emergence of China as a superpower in the 21st century will create many opportunities and challenges for the next president. I say re-emergence because up until 1830, China along with India, had been the dominant economies of the world accounting for about 50% of global GDP (see chart). China is currently the world’s second largest economy. A 2015 report by the Economic Intelligence Unit forecasts that it will surpass the United States to become the leading economy by 2026.

Image credit: http://fatknowledge.blogspot.com.au/

As it re-emerges as the leading global economy, China will increasingly assert itself on the world stage. It has started to do so in its own backyard, the South China Sea. Robert Kaplan likens China’s moves to that of the US when it was emerging as a superpower, when he wrote

Merriden Varral of the Lowy Institute says that aside from the importance of the South China Sea to international trade routes and as a potential source of energy, China’s motivations for asserting itself in the region come from a deeply held view regarding what it sees as “its rightful and respected place in the world… after the painfully remembered ‘Century of Humiliation’ beginning with the Opium Wars in the mid-1800s.” She goes on to say

China observes relationship-based governance, that is predicated on norms of reciprocity rather than a system of rules. Varral contends that if the International Court in the Hague decides in the Philippines’ favor to invalidate China’s territorial claims, China is more likely to react negatively and declare an air defense identification zone (ADIZ) in the South China Sea just as it did in the East China Sea.

An ADIZ is described by David Welch as “a publicly defined area extending beyond national territory in which unidentified aircraft are liable to be interrogated and, if necessary, intercepted for identification before they cross into sovereign airspace.” China’s installation of a powerful radar station and surface to air missiles on different islands in the South China Sea have boosted its capacity to monitor ships and planes passing through the Straits of Malacca, a critical shipping route between Malaysia and Indonesia, according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

The US and its allies in the region have been ramping up rhetoric, in anticipation of this decision, but this tactic runs the risk of reinforcing China’s view of the world ganging up on it, once again. The next president will have to engage with China diplomatically along with other players in the region to ensure that peace and stability is maintained, to enable our economies to prosper and continue to take advantage of the Asian Century.

SPREAD OF ISLAMIST IDEOLOGY

The spread of Islamist ideology is the last challenge the next president has to deal with. In March this year, the chairman of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, Al Haj Ebrahim Murad declared that ISIS would gain a foothold in the Philippines, if the next president failed to rescue the stalled peace process. This came after IS attacks in Jakarta had many security experts fear that the southern Philippines would be next. The leaders of Abu Sayyaf, which has links to Jemaah Islamiyah, a Salafi jihadist group, inspired by the same ideology as al-Qa’ida, have previously pledged allegiance to Islamic state.

The Islamic state, like al-Qaeda belongs to the jihadi school of thought, which seeks to reorder government and society in accordance with Islamic law, or Sharia. Late-20th century jihadism was influenced by the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt which promoted the restoration of the caliphate as the ideal system for the Islamic world, and Salafism from Saudi Arabia, a theological movement from within Sunni Islam, which seeks to purify the Islamic faith from idolators (shirk) that detract from the oneness of God (tawhid). According to the Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought,

The Sunni branch of Islam believes that as a head of state, a caliph should be elected by Muslims or their representatives, while followers of Shia Islam, believe a caliph should be an Imam chosen by God from the Ahl al-Bayt (the “Family of the House”, Muhammad’s direct descendants).

Salafis consider themselves to be the only true Muslims. They are opposed to what they see as the excessive veneration practiced by Shi’a muslims of the Prophet Muhammad’s family. Many salafis are also opposed to democrats, for assigning “partners” to God in legislation, which they see as the sole prerogative of the Divine legislator. As Cole Bunzel wrote

The Islamic State of Iraq began in 2006 and gained international recognition when it announced its plans of expanding into Syria in 2013. It rebranded itself as the Islamic State of Iraq and Sham, and after occupying most Sunni areas in the area in June 2014 declared itself a caliphate, or global Islamic empire. In November 2014 alone, the BBC recorded over 5,000 deaths worldwide as a result of Islamic State militant operations. Of that total 9 attacks resulting in 50 deaths took place in the Philippines (see chart).

ISIS attacks recorded in November, 2014

Source: BBC

The Bangsamoro Basic Law, which embodied the peace agreement brokered by Malaysia between the Philippine government and the MILF failed to clear congress after an encounter resulted in the death of 44 government special action forces in January 2015. The law would have increased the geographic area and powers of the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao and would have given this region a greater share of internal revenue and mining royalties. Congressional leaders feared that the would have given away too much power and autonomy, and created a state within a state.

It will be up to the next president to come up with a lasting peace agreement that would be amenable to the various stakeholders in the south. Failure to do so could pave the way for a greater influence of Islamic State operatives in the country, which would have significant repercussions for the growth and stability of the region.

Related Posts

10 Reasons to pass the RH bill now

The Next President We Want

CHEd….Weather Art Thou?

About The Author

Emmanuel Doy Santos

The author works as a development consultant and policy analyst in Adelaide, South Australia and Manila, Philippines. He is also the founder of the 2Klas Program, which equips inner city youth in Metro Manila with 21st Century skills. He has a Facebook page @CuspPH and tweets as @cusp_ph. He blogs and hosts a podcast on htttps://cusp-ph.blogspot.com.