Duterte’s drug war pales in comparison to the Americas’

So much has been said about the drug war, that is being waged in the Philippines by Pres. Rody Duterte. The Guardian called it “out of control” and “one of the world’s bloodiest anti-drug campaigns”. The Washington Post described it as “horrifically violent”.

Graphic images of drug suspects murdered on the streets of Manila were depicted in a Pulitzer Prize winning photo essay featured in the New York Times, with a caption that read, “They are slaughtering us like animals”.

The former president of Colombia César Gaviria who battled drug lord Pablo Escobar in the 1990s wrote in a New York Times op-ed piece that Duterte is repeating the same mistakes that he committed.

Human Rights Watch (HRW), a nonprofit organisation, has called on the UN to establish an independent investigation into the killings. It claims that Duterte could eventually be held liable for crimes against humanity.

Duterte’s office counters that the media is full of bias, aiming to mould public opinion against him by over-dramatising what is happening in the Philippines. There is already some evidence that public support for the drug war has waned.

Disputed figures

A Rappler article claims that since July 1, 2016, there have been 7,080 people killed in Duterte’s war on drugs. This figure is often cited by international journalists, human rights activists and even the Vice President when she addressed the UN, recently.

It has been disputed by a pro-Duterte blogger named Thinking Pinoy, who says it came about by some dubious arithmetic (adding the number of deaths of suspected drug personalities to the number of victims in cases of deaths still under investigation and concluded, which may not be drug related at all).

Gauging the brutality of Duterte’s anti-drug campaign is no easy task, given the hazy definition of what constitutes a drug related investigation, the cases of vigilante killings and the problem of verification.

To address this, I decided to use the intentional homicide rate as a proxy measure. Intentional homicide or murder is distinct from simple homicide in that the perpetrator intended to kill the other person, in some cases with premeditation. This is a proxy measure since intentional homicides cover both drug and non-drug related killings.

But because it is reported annually, we can compare the “before-and-after” picture of Duterte’s war on drugs. Any unnatural growth after he took office can be attributed to his new drug policy. The World Bank compiles intentional homicide rates as well, which allows us to make comparisons with other countries that have waged similar anti-drug campaigns.

Comparative cases

I have chosen three other nations from the Americas to compare with the Philippines. These are Mexico, Colombia and El Salvador, which have prosecuted their own violent anti-drug wars.

Colombia in the 1990s waged a campaign against the Medellin cartel headed by Pablo Escobar and the rival Cali cartel. This morphed into Plan Colombia, which received $7.3 billion in military and economic aid from the US Congress throughout the 2000s.

Mérida Initiative was the Mexican government’s approach to the war on drugs. Since 2008, the US Congress has appropriated $2.5 billion to back this drive. Mexican authorities were able to arrest top crime leaders, including Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman in 2014, who was extradited to the US in 2016.

In El Salvador, violence erupted after a government brokered truce between two rival gangs involved in illegal drugs fell apart in 2014. The government created a special force to impose an “iron fist” or Mano Dura to restore law and order. The violent crackdown that followed turned El Salvador into the murder capital of the world in 2015.

Before and after Duterte

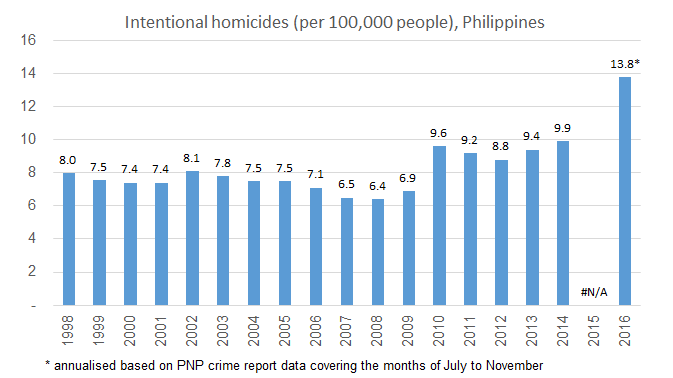

Using published data from the World Bank, we can look at past intentional homicide rates in the Philippines, and compare them with Duterte’s first months in office. I am using the murders recorded by the Philippine National Police covering the period of 1 July to 30 November 2016, as reported by ABS-CBN for the latter.

In the first five months of the Duterte administration, a total of 5,970 murder cases were recorded. This was an increase of 51% compared to the previous year. If the murders continued at this rate, it would result in over 14,000 deaths at the end of 12 months.

With an estimated population of 104 million, this would translate to 13.8 intentional homicides per 100,000 people, a 40% increase compared to the rate of 9.9 in 2014, or roughly 4,000 more deaths. This would represent a significant rise, which can be attributed to Duterte’s anti-drug policy, for the most part.

It is not entirely attributable to him since the murder rate was already on the rise, but it does represent a significant break from the past. However, that assumes that the murder rate continues for the rest of the fiscal year, which might not necessarily happen.

The Guardian reported that after the killing of a South Korean businessman in police custody back in January, the rate of drug related murders has declined to 69 in March, from hundreds in Duterte’s initial months. The annualised rate I have derived will probably exceed the actual for Duterte’s first year.

Benchmarking with the Americas

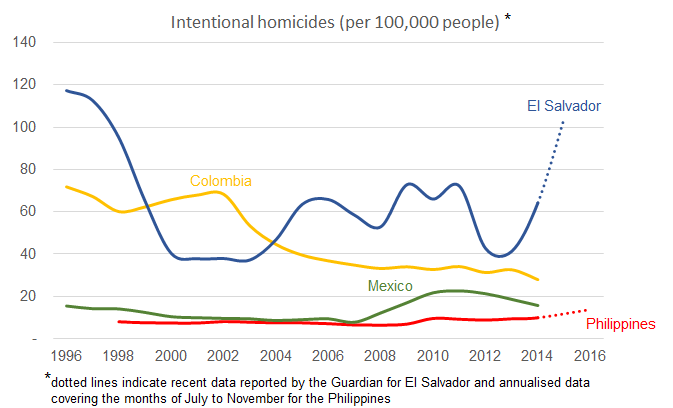

We can now compare the intentional homicide rates for the Philippines, Mexico, Colombia and El Salvador (see chart). I included (in dotted lines) the latest record for El Salvador in 2015 (reported in the Guardian) which is our data point for Mano Dura, and our annualised rate for Duterte’s first five months.

When compared to El Salvador, the drug war in the Philippines looks a lot less bloody. The same applies to Colombia in the 1990s, at the height of their war on drugs. Mexico from 2008 to 2014, would be the most analogous to the Philippines, and is perhaps an indication of where we might be headed.

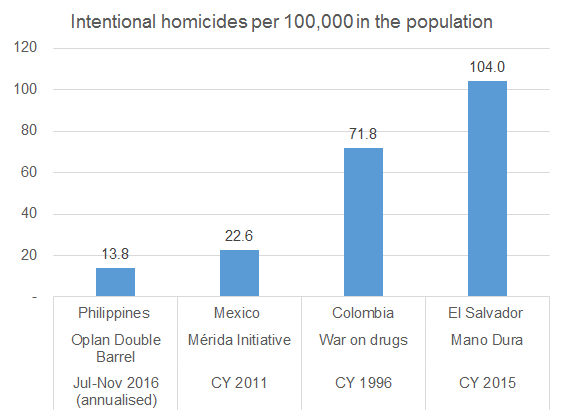

In the next chart, I compare Duterte’s record in his first five months with these Latin American nations at the height of their anti-drug campaigns when their murder rates peaked. These are the calendar years 2011 for Mexico, 1996 for Colombia, and 2015 for El Salvador.

Philippines – author’s calculations based on PNP data, Mexico and Colombia – World Bank, El Salvador – The Guardian

When stacked up against its counterparts in the Americas, the Philippine drug war seems a lot more subdued with 13.8 murders per 100,000 people, compared to 22.6 for Mexico, 71.8 for Colombia, and 104 for El Salvador. For the sake of transparency, I include the table, which was used to construct this chart.

| Country | Campaign | Intentional Homicides | Period covered | Population (in millions) | Deaths/ 100,000 annualised |

| El Salvador | Mano Dura | 6,657 | CY 2015 | 6.40 | 104.00 |

| Colombia | War on drugs | 27,315 | CY 1996 | 38.10 | 71.79 |

| Mexico | Mérida Initiative | 23,068 | CY 2011 | 115.70 | 22.60 |

| Philippines | Oplan Double Barrel | 5,970 | CY 2016 (Jul-Nov) | 103.90 | 13.79 |

Implications

Given the analysis above, is the media’s characterisation of Duterte’s war on drugs accurate? When we look at the raw data, we might be inclined to believe so. But when we set it in historical and international context, it doesn’t seem to be as bad.

Of course, any death, resulting from unlawful action or involving an innocent party, is one death too many. Extra-judicial killings, and any actions used to cover them up should be investigated and prosecuted fully. That goes without saying.

However, the foreign press didn’t seem so preoccupied with highlighting similar incidents in Colombia or Mexico, under the US sponsored drug war. There were no calls to file cases of crimes against humanity against their presidents, when their death toll was much greater.

On a personal note, I have spoken to a Colombian colleague who lived in Medellin at the height of the drug war in the 1990s. He said it was literally a war zone. Only time will tell whether the violence in the Philippines rises to that level. My sense is that it has probably already peaked.

Related Posts

2013 Automated Elections: From BAD to WORSE, Comelec is now anointer of presumed winners

Schedule: 25th Anniversary of the EDSA People Power Revolution

Unilever Philippines Statement: Ads Pull out on ALL live game shows across all networks

About The Author

Emmanuel Doy Santos

The author works as a development consultant and policy analyst in Adelaide, South Australia and Manila, Philippines. He is also the founder of the 2Klas Program, which equips inner city youth in Metro Manila with 21st Century skills. He has a Facebook page @CuspPH and tweets as @cusp_ph. He blogs and hosts a podcast on htttps://cusp-ph.blogspot.com.