World Press Freedom Day Report: State of Media Freedom in PH

State of Media Freedom in PH

World Press Freedom Day Report

May 3, 2020

A Joint Report by the Freedom for Media, Freedom for All (FMFA) Network,

composed of the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility

(CMFR), National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP), MindaNews,

Philippine Press Institute (PPI), and Philippine Center for Investigative

Journalism (PCIJ)

Introduction

The period saw the long awaited decision from the trial of the accused of the massacre of 58 persons, including 32 journalists in Ampatuan, Maguindanao; promulgated at the end of nearly 10 years.

But this high point did not lighten the dreary landscape of press freedom. It is not that surprising that the space for freedom of expression and press freedom has been further constricted in the fourth year of the Duterte administration – the period under discussion in this report, from January 2019 to end of April 2020.

President Rodrigo Duterte had never pretended to be a press freedom champion. He made this clear, when, in 2017, a year after taking office, he singled out for intimidation three news organizations which were actively investigating the number of victims in his centerpiece program, the “war on drugs.” He presented a model of animosity toward journalists who reported critically, raising questions about government actions, doing basically what journalists do.

The president’s low tolerance for the adversarial press became common among government officials, including those in local government units (LGU), the police and military. Social media spawned trolls and so-called influencers, as these were “weaponized” to attack the political opposition, those identified with the former administration, groups and individuals, including journalists. The most prominent of the Duterte propagandists were featured on podcasts by the Presidential Communications Operations Office (PCOO) and later received appointments in government.

In his fourth year in office, little has changed, except for the president’s frequent and unexplained absences from office. Duterte has kept control of government, gaining seats for his candidates in the Senate in the 2019 midterm elections, still boosted by high rates of approval in public opinion polls.

Developments have confirmed the trend toward more restrictive measures for the media, with the usual tactics of intimidation and surveillance. The collapse of the peace negotiations in 2017 also unleashed an array of actions against the CPP-NPA-NDF, linking media reporters to these groups. Even in the midst of the profound difficulties imposed by the pandemic on the nation, there has been little change in the outlook of the administration, persisting in the view that a press must be regulated according to its needs.

Pandemic’s Challenge to Media Freedom

With the outbreak of Covid-19, media watchdogs have noted the restricted space for free speech and press freedom, control of media being a part of the authoritarian approach to a health crisis around the world. The Philippines is no exception. Placing the country under lockdown or enhanced community quarantine (ECQ) to control the spread of Covid-19, the Duterte administration has included legal restrictions on these rights.

Media watchdog organizations have sounded the alarm over diminished free expression. The hostility of some national leaders against the news media has trickled down to local authorities, including the police and military. Governments around the world have been quick to include restrictions on expressive freedoms in the array of official responses to control the spread of Covid-19. And yet, open communication has been among the mechanisms used to enhance the effect of government action.

Kang Kyung-wha, the Foreign Secretary of South Korea, which was among the more successful countries in addressing the pandemic, claimed that the government committed to transparency and accountability, as it undertook prompt and coordinated action. This approach, she added, helped to ensure public trust in what had to be done to slow the spread of the disease.

It was counsel that would not be heard much in the Philippines as government foundered with half-measures, a lack of direction, and muddled leadership.

President Duterte’s use of the war metaphor to describe the government’s fight against the virus was emphasized when he spoke on television on March 16 to announce the expansion of the ECQ, also called a lockdown for the entire island of Luzon. A group of top officers of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) and the Philippine National Police (PNP) were seated behind him, upstaging civilian Cabinet officials, as he delivered his message. Government would use law and order measures to ensure public compliance.

Free Expression and Press Freedom among Covid-19 Casualties

Officers down the line of authority have found ways to “weaponize” government directives against targeted groups. Among these are activists and journalists.

After the president announced the Luzon quarantine, the Inter-Agency Task Force for Management of Emerging Infectious Disease (IATF-MEID) headed by a retired general told journalists to secure accreditation from the PCOO. The task force said that only those with the IATF (Inter-Agency Task Force) accreditation ID may be exempted from home quarantine.

Media groups protested the accreditation requirement as an add-on mechanism of bureaucratic control. Given the constitutional provision for the protection of the press, media have submitted to accreditation when coverage entailed limited space for events and briefings. Such physical limitations do not exist for journalists reporting Covid-related news. Government accreditation is generally understood by the Philippine press as a limitation to freedom, access to sources, and the people’s right to know (Philippine Constitution’s Bill of Rights sections 4 and 7.)

While some government agencies have been proactive in releasing information about the health crisis, response to FOI requests has generally been delayed.

The PCOO for instance suspended responding to FOI requests filed during the ECQ albeit multiple Covid-related requests filed on its eFOI portal.

Measures of Control in the Bayanihan Law

On March 23, as directed by Duterte, Congress passed into law Republic Act 11469 or the “Bayanihan to Heal as One Act” giving the president emergency powers that would enable him to quickly respond to the Covid-19 contagion. The law includes a provision penalizing “fake news.” Section 6 (f) of the new law states:

“Individuals or groups creating, perpetrating, or spreading false information regarding the Covid-19 (coronavirus disease 2019) crisis on social media and other platforms, such information having no valid or beneficial effect on the population, and are clearly geared to promote chaos, panic, anarchy, fear, or confusion; and those participating in cyber incidents that make use or take advantage of the current crisis situation to prey on the public through scams, phishing, fraudulent emails, or other similar acts.”

The provision clearly opens up opportunities for any officer, with little understanding of the Constitutional provision, to determine report or social media post to be “fake news.” This provision adds to the danger of random charges based only on unfounded complaints from officials who feel they have been the object of criticism.

Fake News and Cybercrime

In less than a month, by April 20, 60 individuals across the country had been charged by government officials on the basis of this provision.

The most prominent case reported was that of filmmaker Maria Victoria Beltran who posted a “satire” about Sitio Zapatera in Cebu being the epicenter of Covid-19 in the “whole of the universe.” Cebu City Mayor Edgar Labella screen-grabbed her post and threatened her arrest, which indeed happened a few hours later.

The Philippine cybercrime law has also used to curtail freedom of expression in social media during the ECQ:

- On March 27, Julieta Espinosa, a teacher in General Santos City, was arrested without a warrant for inciting to sedition, after she expressed in Facebook her dismay on the slow relief operations and asked people who were hungry to raid a local gym where the government supposedly stock the aid.

- On April 6, Joshua Molo, the editor of the Dawn, the campus paper of the University of the East (UE), was threatened with the charge of online libel. He posted a comment about the government’s poor response to the threat of COVID-19. After a heated exchange with his former teachers on Facebook over his comment, Molo was forced by barangay officials in Nueva Ecija to publicly apologize.

Unfortunately, such intolerance has been accepted by a public in a state of panic. A common message has spread in social media and echoed by some officials, asking that others refrain from criticizing government, because they probably couldn’t do better and that in a time of crisis, citizens should just follow what government asks them to do.

The problem feeds on itself. Given the terrifying threat to life, communities tend to submit to authorities without question. The lockdown prevents the usual tactics of public protest. Government can then flex its muscle with little question, insuring silence and acquiescence of the people. Meanwhile, bungling on the part of government has caused delays in the conduct of sound health measures. Those manning the checkpoints do not follow what has been announced by other officials as the accepted procedure or requirement for citizens who have to travel. It is the duty of the press to publicize these to prod government to become more competent and effective. In reality, the quick action to provide masks and PPEs had been undertaken by the private sector, by individuals and groups acting on their own. Reporting on the shortcomings of officials and their agencies can prod government to do better.

Threats and Attacks vs. Press 2019

Threats arising from the crisis should be seen in the context of the state of media freedom in the past year, a period which has typified the rise of other attacks and threats being reported by the press community since 2016.

From January 1, 2019 to April 30, 2020, CMFR and NUJP documented 61 reported incidents of threats and attacks against the press, including three journalists who were killed.

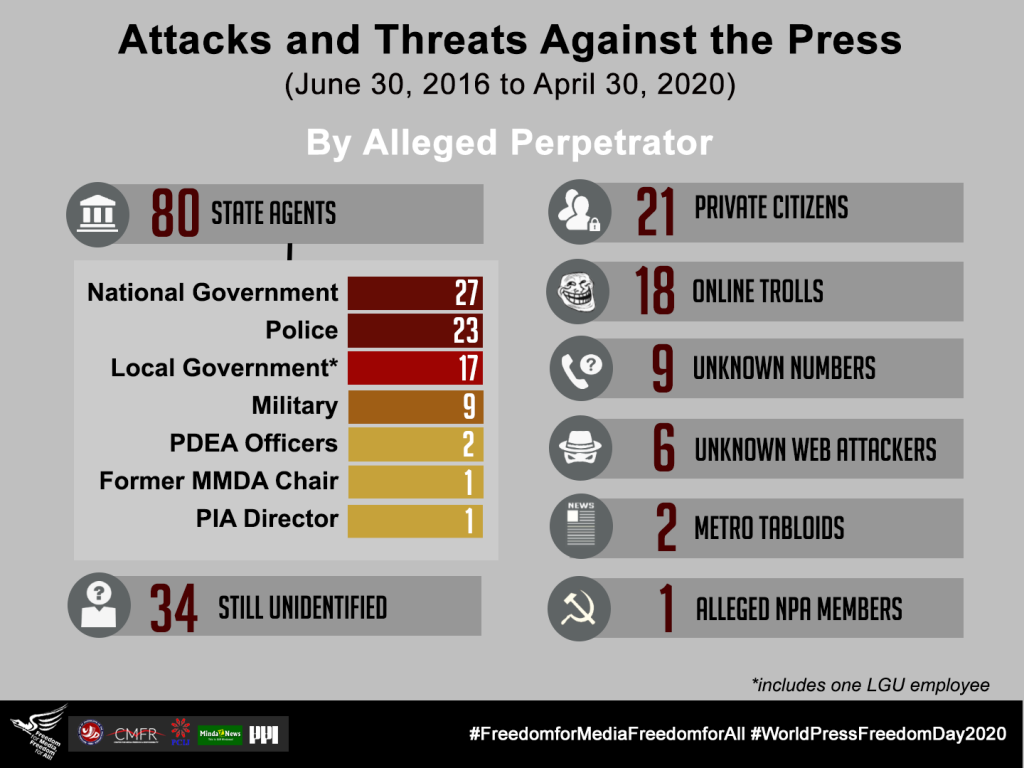

Half, 30 of the 61 incidents, were allegedly perpetrated by state agents; 14 by national government officials in the executive branch, the Senate and the House of Representatives; 11 by the police; three by local government; and, two by the military.

Threat to withhold renewal of ABS-CBN franchise

The most highlighted attack during the period involved the largest broadcast network in the country whose application for the renewal of its franchise has still not been granted by the House of Representatives. A bill to renew ABS-CBN franchise was refiled in the 18th Congress on July 1, 2019. Currently, there are at least nine bills filed for the renewal. The franchise expires on May 4, a day after World Press Freedom Day.

The controversy over the franchise of ABS-CBN builds on the expressed anger of President Rodrigo Duterte, who publicly berated the network for its failure to air political advertising that his presidential campaign had paid for in 2016. He continued to express his animosity toward the Lopezes who own the network, calling them oligarchs. In several separate speeches, the president accused ABS-CBN of fraud and estafa. He started to threaten the non-renewal of the franchise in early 2017 and repeated such threat in some of his succeeding speeches.

On February 10, Solicitor General Jose Calida filed a quo warranto petition in the Supreme Court asking the high court “to forfeit” ABS-CBN’s franchise. Calida enumerated the network’s “highly abusive practices” in his petition. FMFA and other press freedom advocates said that the Calida quo warranto had no basis in law, and was seen only as a gesture to make a good impression on the president.

On February 24, the Senate Committee on Public Services proceeded with a committee hearing to clarify issues in the ABS-CBN franchise and how to move forward. Some argued that the existing franchise is good until the end of the 18th Congress. Justice Secretary Menardo Guevarra said that the National Telecommunications Commission (NTC) can issue a provisional franchise to the network, although this could be withdrawn by the same agency.

The NUJP led a weekly Black Friday protest to call for the network’s franchise renewal. The media community from different organizations, press freedom advocates and entertainment personalities joined the Friday protest events, as national and international media watchdog organizations aired with journalists crossing across organizations to air messages of solidarity and calling on Congress to act quickly on the renewal.

It has to be pointed out that the placement of the franchise authority in Congress needs to be changed. The constructive regulation of bandwidth and other communication issues should not be placed in the hands of politicians.

As of press time, the lower house has yet to discuss the franchise issue.

Red tagging

Red tagging, or red baiting, are actions which publicly link individuals to the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP), the New People’s Army (NPA) or the National Democratic Front (NDF). Some who are red tagged, are not accused of membership in the CPP-NPA-NDF but links with what the military calls “front organizations”. Worst, the military would sometimes subject suspected “reds” to trumped-up charges, among them illegal possession of firearms.

Red tagging has become one of the perils confronting journalists who report on issues and concerns that officials would rather keep secret. It is now seen as a consequence of truth-telling. It is often used to discredit journalists who report on the concerns of peasant or indigenous communities, usually violations of their human rights perpetrated by uniformed men. The pattern of accusation usually targets activists or those working with the alternative media and the community press.

Included in reports are recent incidents which show how red tagging can lead to serious harassment and even arrest:

Frenchie Mae Cumpio, executive director of the Eastern Vista, has been tagged by the military as a high-ranking official of the Communists Party of the Philippines since she started reporting about human rights issues in Tacloban.

On December 13, 2019, her team was tailed by an unidentified man aboard a motorcycle.

Since then, 21-year old Cumpio has received other threats from unknown individuals, including flowers for the dead with her picture. The Tacloban-based journalist also told CMFR on February 6 that masked men have been surveilling their office since December.

On February 7, Cumpio was arrested after the military raided the Eastern Vista office and found illegal firearms and explosives. She remains at detention up to now.

Paola Espiritu, Ilocos correspondent for the Northern Dispatch (NorDis), has been linked with the communists and maligned by the military since 2018, according to NorDis.

On three different occasions in 2020, she was accused of being a member of the NPA by the 81st Infantry Battalion led by Capt. Rogelio Dumbrique.

According to NorDis, “the unrelenting attack against her has taken a toll on her emotional state and made her seek refuge.” [See NorDis report]

Use of soft power to co-opt media communities

Though not included in the count, FMFA is concerned about another kind of intimidation which some media groups have reported in 2019. The National Intelligence Coordinating Agency (NICA) has been holding forums for members of the community media in regions where journalists are “compelled ” to sign off to a “Manifesto of Commitment” declaring their “wholehearted support and commitment to the implementation of President Rodrigo R. Duterte’s Executive Order No. 70 to the Regional Task Force To End Local Communist Armed Conflict.” [See previous FMFA report]

According to those who attended the events, to decline could have been interpreted as going against the Task Force’s supposed goal of ending the “communist armed conflict.”

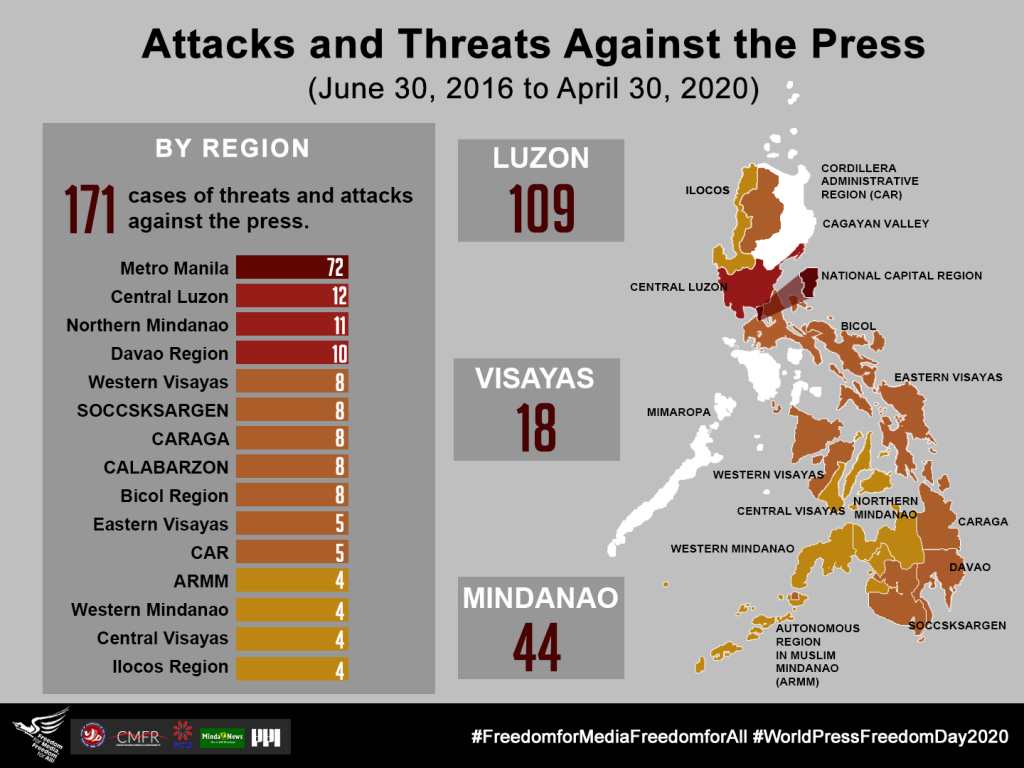

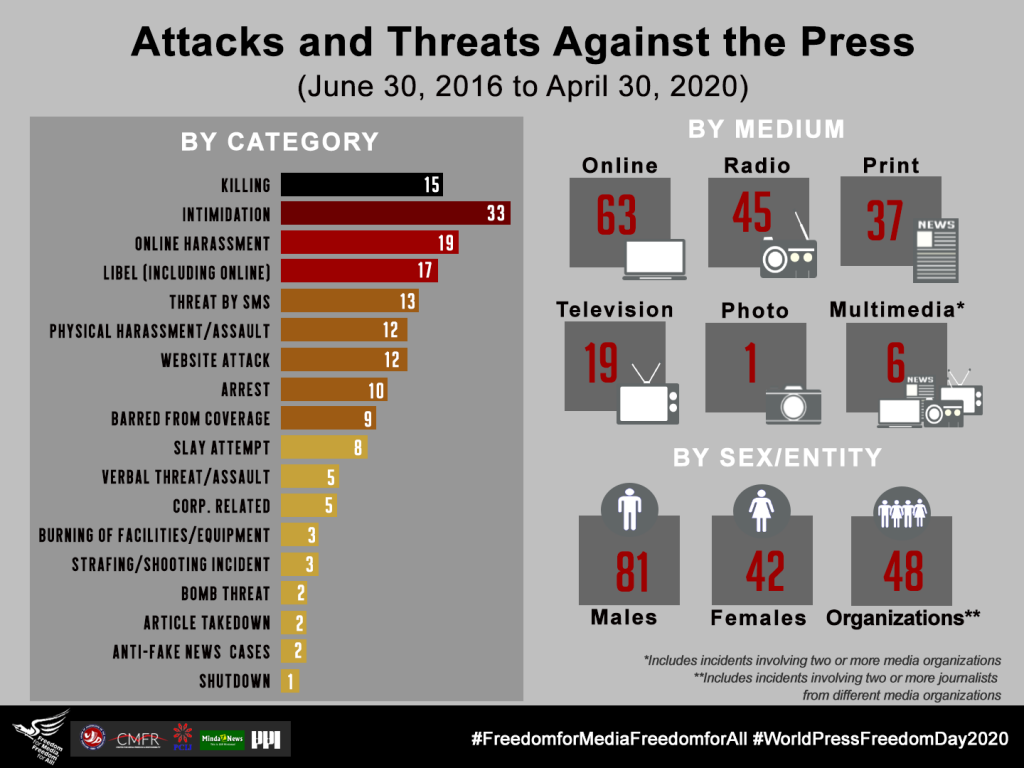

BY THE NUMBERS:

THREATS AND ATTACKS VS. PRESS UNDER DUTERTE ADMINISTRATION (June 30, 2016 to April 30, 2020)

NOTE: Some numbers/data may have changed from previous reports after some cases, upon further investigation/consolidation of data, were proven to be not work-related.

Infographic by CMFR