Surveillance technologies to fight the #coronavirus pandemic must respect human rights

In early March, I wrote my daily activity, including the people I interacted with, in a journal. I thought it might help me later on in case of the conduct of contact tracing of people afflicted with the coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19). My friends were telling me they preferred the “location history” information through the Google Maps Timeline, which is available to both mobile and desktop users. Location history is a Google Account–level setting that saves where you go with every mobile device when you opt in. It serves as an automated diary.

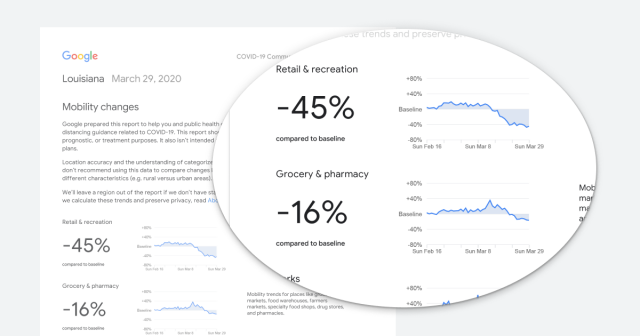

Google’s location history information proved useful in its coronavirus support efforts with last week’s launch of their Covid-19 Community Mobility Reports web tool. Providing insights into what changed in response to policies aimed at combating Covid-19 is the goal of these reports. They plot movement trends over time by geography, across different categories of places such as retail and recreation, groceries and pharmacies, parks, transit stations, workplaces, and residential areas. Preparation of the report is meant to help “you and public health officials understand responses to social distancing guidance related to Covid-19.”

Settings for my Google Maps are set to “while using the app,” but during the times I don’t use the app, nothing registers on my timeline. I checked out the Philippine data as of March 29, 2020. The data reflect mobility information from two or three days prior, according to the company, and never display absolute visit numbers. Mobility trends for places like public transport hubs such as subway, and bus and train stations showed the biggest drop at -82 percent. Following closely at -81 percent are the mobility trends for places like restaurants, cafes, shopping centers, theme parks, museums, libraries and movie theaters. Mobility trends for places of residence show +26 percent, which may not be accurate since not everyone enables location access in their Google Maps setting when not using the app.

What I find useful is a mobile app that makes it possible to warn me about proximity to infected patients. I don’t plan to go outside my home during the enhanced community quarantine, but when it is lifted, a contact tracing app with continued mass testing would help fight Covid-19. National Privacy Commission Chairman Raymund Liboro told Inquirer that they are assisting a team of 15 software engineers and designers from the University of the Philippines to launch a new contact tracing smartphone app to aid its fight against Covid-19. The app would share features with the Singaporean government’s “TraceTogether” mobile app, but enhancements would need to be added since not everyone uses a smartphone.

The TraceTogether app, launched in Singapore last March 20, works by exchanging short-distance Bluetooth signals between phones to detect other app users within two- to five-meter proximity. If an app user tested positive for Covid-19, authorities could identify other app users in close contact with the patient, as records of encounters between the app users would be stored in the users’ phones.

Another app, WeTrace.ph, developed by Cebuano information technology developers, assigns unique QR codes to every user to protect their privacy, uses geolocation data for contact tracing and keeps track of other users nearby. No other information is collected by the app. When a user gets infected, authorities check its WeTrace data for contact tracing, just like TraceTogether. Only Android users could use the app right now since the developers are still waiting for Apple’s approval.

Smartphone tracking, combined with mass testing, can help create a framework for cities to let people resume their lives, even after the lockdowns. Sharing location is not always bad if location-based apps provide disclosures and helpful services. South Korea, China and Israel have already deployed surveillance tools or versions of tracking apps against the Covid-19. Austria, Belgium, Italy, the United Kingdom and Germany were gathering anonymized or aggregated location data from telecommunications companies, according to Amnesty International. Other countries are using cellphone data without the added protections of anonymization or aggregation. Ecuador’s government, for instance, authorized satellite tracking of citizens included in the epidemiological fence. Respect of human rights is being called out by Amnesty International when digital surveillance technologies are used by states to fight the pandemic. Their position is that “surveillance measures must be the least intrusive available to achieve the desired result. They must not do more harm than good.”

As originally posted on Sunday Business & IT, April 12, 2020.