The integration of poverty alleviation in the strategy for economic growth

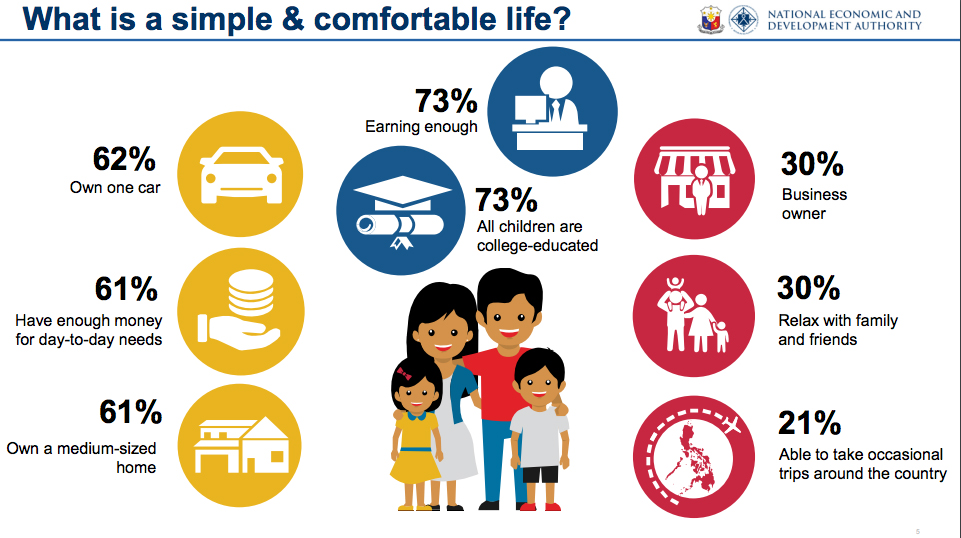

Filipinos want to live a “simple and comfortable life.” The National Economic and Development Authority or NEDA’s “Ambisyon Natin 2040” Report shows 79.2 percent of Filipinos want a simple and comfortable life that includes a college education for all children; to earn enough money to purchase day-to-day needs; own a car and a medium-sized home; own a business; have time to relax with family and friends; and be able to take occasional trips around the country. The sad thing is there are 26.3 percent or roughly 26 million of the 100 million Filipinos living below the poverty line, according to data from the Philippine Statistics Authority as of the first quarter in 2015 . Finance Secretary Carlos Dominguez III plans to reduce poverty rate between 1.25 and 1.5 percentage points a year which will make a combination of around nine percentage points. Is that possible?

Let us look at the Vision of Filipinos for Self that came out from the Ambisyon Natin 2040 report:

“In 2040, we will all enjoy a stable and comfortable lifestyle, secure in the knowledge that we have enough for our daily needs and unexpected expenses, that we can plan and prepare for our own and our children’s future. Our family lives together in a place of our own, yet we have the freedom to go where we desire, protected and enabled by a clean, efficient, and fair government.”

President Duterte was criticized by Former President Fidel Ramos for not having a long-term strategic vision for the country. After a few days, President Rodrigo Duterte signed Executive Order (EO) No. 5, “which adopts “Ambisyon Natin 2040″, 25-year long-term vision of NEDA to wipe out poverty and hunger in the country.” The fact that the President adopted the Aquino administration’s Ambisyon 2040 is good for the continuity of governance. The vision came in during the latter part of the Aquino administration and in itself isn’t clear about how the vision will be achieved.

The Executive order says that “The Philippine government hereby aims to triple real per capita incomes and eradicate hunger and poverty by 2040, if not sooner”. Four Philippine Development Plans (PDPs) will be crafted and implemented until 2040, all anchored on Ambisyon Natin 2040. Just like the vision of the Filipinos , the government envisions itself that “by 2040, the Philippines shall be a prosperous, predominantly middle-class society where no one is poor. Our peoples will enjoy long and healthy lives, are smart and innovative, and will live in a high-trust society.”

During the Ramos administration, the President offered a simple battle cry: Philippines 2000. A report by Maria Teresa Diokono Pascual explained why this vision failed. Ramos ” relied on the elite to get his gameplan going. President Ramos? commitment to ending poverty was little more than an imagebuilding project that lacked real substance. This was the other serious flaw of the Ramos economic project: its failure to integrate poverty alleviation in the strategy for economic growth. At best it treated its social reform program as an afterthought to growth. As such it could not resolutely alter existing inequalities in income and the distribution of the benefits of growth. Because it failed to address poverty and social inequality, the Ramos economic project was not sustainable.”

President Duterte needs to learn from the mistakes of the past administrations . A cursory look at the “Philippine government’s own conceptions of poverty and poverty reduction” from 1986-2010 is instructive. The PNoy administration’s anti-poverty strategy , the Pantawid Para sa Pamilyang Pilipino (4Ps) otherwise known as the Conditional Cash Transfers is a short term strategy. Solita Monsod, socio-economic planning minister under his mother’s presidency observed that the first dozen years of the post-EDSA regime (from Cory Aquino to Fidel Ramos, 1986-1998) fared better in poverty reduction than the last dozen (from Gloria Arroyo to Noynoy Aquino, 2003 to present). Poverty incidence fell from 36.5% to 20.5% in the former, while remaining flat in the latter.

The Challenge

In our previous article on “The Post-PNoy Presidency,” , Emmanuel Doy Santos suggested that “the appropriate policy levers for our stage of development should now be obvious as follows:

- Asset reform that assigns full property rights for the poor to access formal credit markets,

- Adequate delivery of basic health and educational services, including vocational and technical training,

- A vigorous policy of industry engagement and coordinated action to encourage risk-taking, adoption of new technologies, and provision of complementary infrastructure and other “club goods”.

Duterte’s short term strategy is developing the countryside to lift around nine million Filipinos out of poverty in six years as discussed in the Sulong Pilipinas workshop in June 2016. The possibility of attaining the long term vision by the year 2040 depends on the policies adopted to foster growth and reduce social inequality over the coming 25 years. That vision will be achieved gradually, through reforms sustained over four succeeding administrations.

Under NEDA’s projected ‘best case’ scenario , the eradication of poverty could happen as early as 2030, ten years earlier than under the worst case scenario of slow, unequal growth. Mastering the functional capabilities to produce these outcomes should come first. President Duterte can now open a new chapter in our nation’s history to help achieve the vision of the Filipinos for the country:

“The Philippines shall be a country where all citizens are free from hunger and poverty, have equal opportunities, enabled by fair and just society that is governed with order and unity. A nation where families live together, thriving in vibrant, culturally diverse, and resilient communities.”

It is now the task of the Duterte administration to articulate how this vision will be achieved.

This post is supported by a writing grant from the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ)